In the metaphorical story of Raktabeeja, a simple act of a mere drop of his blood touching the ground can create an exact replica of him each time the drop touches the ground. In the larger scheme of things, it’s an apt metaphor of all that is vile but able to replicate, with its structurality already ascertained, its outcome pre-ordained. Lesser mortals in their deluded endeavour to exterminate all that is lustful, try mistakenly to end the tyranny of the demon by slaying it. This act of trying to injure or do away with his existence actually amplifies his power, thus making an already precarious battle all the more complicated. Perfect replicas of him spring up at the mere touch of the ground and instead of the intended annihilation, one has a fastly replicating chain-reaction-like situation to contend with.

The antidote to a structural Raktabeeja then is digestion, and not the unimaginative approach of slaying. It requires the mettle of the one proficient at killing all illusions. The structural nature of the parasitic seed must be first comprehended properly for it to be swallowed and then digested; as a countermeasure for its end. The seed is so poisonous that it needs the intervention of the great Mother Goddess herself for the success of such a phenomenon.

It is an apt metaphor for all that is seemingly insurmountable or keeps multiplying virulently. The case in point here is the invisible ties of the demon that is colonialism. One has to just glance at the situation of several countries of the Global South to understand the similarities of destroyed economies, slain leaders, overturned governments, dwindling cultural wealth and natural resources to gauge the structural similarities. The most glaring of the similarities are in the way it manages to fracture previously held unities, ideas of self, society and community of the earlier natives and manages to wreak war amongst fraternities, tribes, cultures, geographical and psychological boundaries of identity, cast arbitrarily by the colonizer, as it were, in stone. To understand its replicating structure one has to study its effects in depth at one point of its intervention, the pattern then is applicable to all kinds of relationships between the colonizing force and the colonised. From slaves on the plantation to indentured labourers to the immoral plunder of natural resources, the applicability of the pattern is discernible once made visible by reflective insights into existing research. The deep dive into available records this time is the changing status of some of the groups that were the avarnas and came to be known as the “criminal tribes” after several British interventions, namely the Chamars and the Mahars.

From sweatshops to malls

An aimless stroll in one of the several posh, air-conditioned malls of South Delhi inevitably brings to your notice the numerous shiny signages of the topmost leather brands of India and the world – Hidesign, Esprit, Mango, Armani and many more. The over-friendly salesperson with her carefully adorned beaming smile seems to compensate for the not-so-friendly prices of the luxury items on display, which are beyond the reach of most visitors. It is a world of make-believe, where most Indians go window shopping to absorb the five-star vibes of glamour and global capitalism, triggering in them a short-lived euphoria and a long-term aspiration for the ‘good life’, a euphemism for the third-world desire to be first-world. Little do they know that the edifice of one good life can only be built on the foundation of the misery of thousands of unseen others, just as the modern west was built from the plunder of Asia and Africa by the demon of colonialism.

The leather industry is one of the most polluting industries in the world on account of the highly toxic chemicals like Chromium, Lead and Arsenic used in the tanning process. Between the skinning of animal carcasses to the display of footwear and bags in shiny malls in South Delhi or downtown Paris, the manufacturing process includes around fifteen operational steps, each of which generates contaminants that adversely affect the quality of water, air and land exposed to these toxic effluents.1 It should come as no surprise that the workers employed in the leather industry, exposed to these toxins for the better part of their working day, suffer from all kinds of debilitating health conditions ranging from asthma to tuberculosis to skin cancer and discolouration. To make matters worse, the toxins do not spare the foetuses, often leading to congenital mental disabilities in the children of leather workers. The industrial zones that produce most of the leather in the country like Kanpur, Agra and Ambur have suffered a massive degradation of soil quality, making large tracts of agricultural land unfit for cultivation.2

India ranks fourth in the global list of leather-producing countries and its status of being a major source of leather in the world has remained unchanged since colonial times. The industry employs close to 4.5 million people in India and the products find their way to the USA, UK, Germany, Italy, UAE, and a host of other rich countries.3 After independence, there has been a massive push by the government of India towards the export of semi-finished or finished leather products instead of raw or semi-processed animal hides because it makes clear economic sense. The skin of one animal, which costs under $2, can produce as many as 6 pairs of shoes, each of which could easily be sold for $100. Therefore, from 1947 onwards, India has seen a proliferation of leather processing units, specifically in the small-scale sector.4

The government policy of promoting small-scale units was based on the rationale that this would ensure that the large number of people engaged in traditional leather production would be absorbed in the labour-intensive small-scale tanneries and it would also preserve their traditional skills. It is debatable how successful the policy was in achieving its stated objectives but it can be said with certainty that the change in policy at the turn of the millennium to modernise the industry led to a financial crisis for the communities that dominated the small-scale leather sector, namely Chamars. A huge number of Chamar entrepreneurs lost their businesses and were turned into workers in the modern leather processing units.

There is an important angle to this story that is often ignored, which is the western aversion to highly polluting industries and their ironic, and almost addictive, dependence on their products. Since leather is in high demand in the west and producing it is messy to say the least, the job has been transferred to the third world, thereby taking advantage of the power asymmetry between the two spheres. Producing leather while keeping the pollution in check is technically possible but commercially a non-starter. Therefore, ‘developing’ countries like India, where the environmental norms exist only on paper and where the health of citizens is at the bottom of the State’s priority list, become ideal production hubs to meet the high demand of leather in the ‘developed’ world. Environmental regulations on the leather industry are superficial PR exercises even in China, also the largest exporter of leather, simply because the associated costs put the product at odds with its affordability in the global market.

Given these realities, it would be reasonable to expect economists, industry experts, academicians and politicians to invest all their energies in evaluating the ‘human cost of leather’ and to work out a viable long-term solution, whatever that may be, to the environmental degradation, health crisis and labour exploitation that has become an integral part of industrial leather production today. Instead, they choose to wriggle out of the tight spot and blame these obvious systemic failings of modern global capitalism on – hold your breath – the caste system.

A note on Balutedari

At this point, it is useful to examine how leather was produced in pre-British India, which communities produced it, what kind of relationship they had with the rest of the society and how all that compares with the current social status of leather workers as mentioned in the preceding paragraphs. As an illustrative example, let us take the case of the Mahars, a present day scheduled caste from Maharashtra, whose most iconic representative in our times is the first law minister of India, Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar.

Mahars were one of the twelve Balutas or Balutedars, a group of service providing communities that also included Sutar (carpenter), Lohar (blacksmith), Chambhar (cobbler), Parit (washerman), Kumbhar (potter), Navi (barber), Mang (rope-maker), Kulkarni (village-accountant), Joshi (astrologer), Gurav (non-brahmin Shrine keeper) and Potdar (money-assayer). Grant Duff, an early British soldier and historian, documents the main duties of the Mahar as portering, carrying letters from one village to another, keeping vigil, attending to travellers, acting as a guide, and occasionally scouting and spying. Mahars also played a key role in the resolution of inter-village land disputes as they knew the area better than everyone else. In return for these services, the Mahars were entitled to a grant of rent-free land by the government. This was called Chakri-watan. They were also given land grants by villages directly, called Hadki-Handola, in exchange for services like skinning the dead cattle within the village boundaries.5

A detailed investigation into the nature of the Balutedari arrangement and its power dynamics is out of the scope of this essay but will be covered in detail in our book. Suffice it to say here that contrary to their depiction as landless labourers exploited by upper caste land-owners under the influence of ‘Brahmanism’, Mahars were an integral part of the Maharashtrian village who were respected and whose opinions were given great value in legal disputes. In fact, any violence against them was treated as a criminal act and a heavy fine of Rs. 50 was charged from the transgressor.6 In his fieldwork carried out as late as the 1950s, Henry Orenstein noted that Mahars were among the highest-paid groups in the Balutedari scheme, with their earnings exceeding those of the higher Balutedar castes like Sonar and Gurav.

It must be pointed out here that Balutedari was not an exceptional arrangement peculiar to Maharashtrian society but rather a norm all over India. In the North, it was known as the Jajmani system and while each sub-region had its particular flavour of organisation, the fundamental characteristics of interdependence were common. Sociologically speaking, there are two theoretical approaches to understand the Balutedari/ Jajmani system: Functional and Marxian. The former views it as a socially integrating system while the latter conceives the village as divided into two classes defined in terms of their relationship to the means of production. Based on his extensive fieldwork, Orenstein defends the functionalist character of Balutedari and asserts that it cannot be construed as an exploitative system. He adds that the village is a cohesive unit in such an arrangement and takes precedence over caste. He observes,7

As I have observed, balutedars divide the work among themselves by allocating time or the land of the village, not households of landowners. This gives reasons to believe that the balutedar sees his tie as one between his group and village as a whole, rather than as a person-to-person relationship. In this region, a number of people live outside the main settlements of their village, many on distant farms. Some of these are closer to the main settlement of other villages than to their own, yet I found no one who attended religious ceremonies of other villages. Everyone who is able, both Balutedar and landowners, make financial contributions to village affairs. Caste conflicts are strongly discouraged at ceremonies. People even disparaged their own caste fellow in order to placate the other and thus maintain harmony. In wrestling contests, people cheer athletes from their own village, irrespective of caste.

It is also this relatively “free” system of organisation that takes care of each artisan by providing for cultivable land, food, occupation, and social participation in festivities that allows for a flourishing of individual innovation not just in terms of technology but in terms of products made. From shoes to water carriers to purses to boats and rafts, from buttons and decorative pieces to drums to secret tanning recipes, the kind of organic growth of production and its intricate relations to natural resources and ecosystems should have formed the bulk of Marxian research only if one was willing to first acknowledge the uniqueness that the traditional forms of production that Indian artisans hold in the world markets.

Enter the Briton

By the time the East India Company monopolised the European trade with India, the subcontinent was all set to be the proverbial jewel in the British crown. With exponentially growing trade accompanying the Industrial revolution, more Britons were setting foot in India than ever before. India, the exotic land of spices and snake-charmers, had such an abundance of human and natural resources that it was presumably impossible for the Company Bahadur to let any moral considerations dampen their unbound capitalistic spirit. One of the things that astonished the visitors was the sheer number of cattle and their venerable place in Hindu society.

In the eighteenth century, leather production within the ‘primitive’ milieu of the native economy was a cottage industry that went back several thousand years and employed natural ingredients to carry out the tanning process. Barks and pods of trees native to a particular region were used to extract the natural substances that were applied to the raw hides, which came from dead animals.8 In the accompanying pan-India rural economic system of Balutedari/Jajmani, the equivalent of Chamars flayed the dead animals, tanned the hides, converted the leather into footwear, ropes, drumheads, and so on and supplied the products back to the villages without the involvement of any middlemen. Only the surplus goods were supplied to urban tanners and markets. This too was a kind of monopoly, where the jajman’s dead animals automatically became the property of the chamar, no questions asked. As mentioned earlier, this was done in exchange for various privileges for the Chamar like rent-free land grants, free timber, share in the annual harvest, access to grazing grounds, etc.9 In the great urban centers of India, the leather craftsmen, like the practitioners of other trades, were organised into srenis or guilds and exerted considerable influence on policymaking.10 However, what the modernising gaze of the coloniser did to this primitive milieu of eco-friendly production, harmonious distribution and self-regulated growth is a tragic story.

Dawn of a dark new era

The inevitable modernising of leather production in North India is attributable to the native revolt of 1857 with the establishment of the British Government-owned Harness and Saddlery Factory in Kanpur by 1867.11 The factory was set up to supply leather equipment to the entire imperial army in India. Soon, Kanpur began seeing the mushrooming of private tanneries supervised by the British government, and became the hub of leather production in India. But there were two major changes that accompanied the growth of the modern industry:

- A shift from natural to chrome-based tanning

- Hides began to be sold at ‘market price’

While the shift to chrome-based tanning was a technological choice that very quickly began to negatively impact the health of the workers and the natural environment of cities like Kanpur, the new price tag attached to the dead animal was disastrous for the social and financial security afforded to the chamars in the traditional scheme. As the new leather industry grew exponentially, its appetite for dead cattle increased proportionately. The invisible hand of the market thus kept pushing the price of the dead animal further up, which is another way of saying that the cattle began to be seen as more valuable dead than alive. This idea was abhorrent to the majority of cattle owners, who as Hindus worshipped the animal and therefore, the Hindu merchants would have nothing to do with this new industry, which they saw as an embodiment of sin and turpitude. But the religious imperative did not prevent Hindu cattle owners from selling the dead cattle for a handsome price to the new traders instead of handing it over to the Chamar for free. As John Briggs observed,12

The increased value of leather has led the landlord to question the chamars’ traditional right to raw skin.

By the turn of the century, this very profitable trade came to be dominated by Muslims, a large number of whom had become extremely wealthy in the process. In contrast, the traditional Hindu leatherworkers – Chamars, Mahars, Dhors, Madigas, Chakkiliyans – whose source of income had been irreversibly and profoundly disrupted, either turned to agriculture for basic self-sustenance or moved to the urban leather manufacturing hubs in search of employment in the factories.

Of famines, criminals and slums

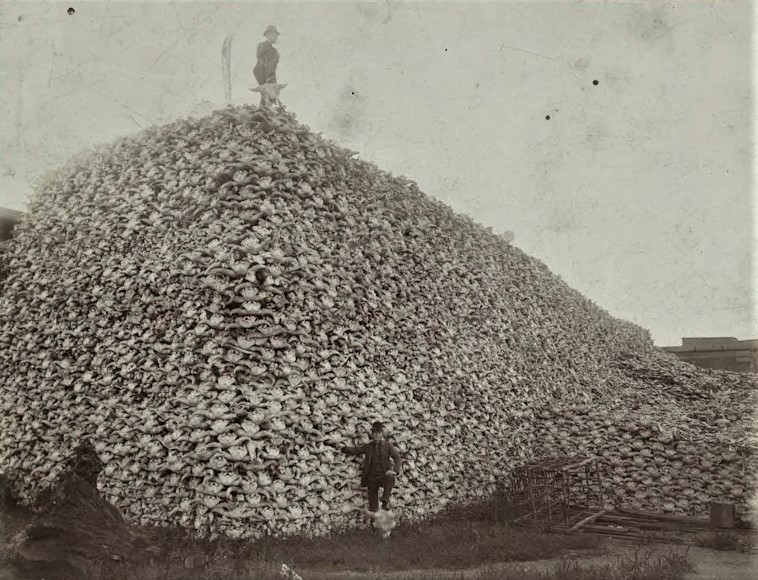

As if the turn of events was not catastrophic enough for the leatherworkers, the days of the Raj turned even more unbearable with one famine after another striking the land, which directly led to a huge spike in cattle mortality and an almost infinite supply of hides for the industry.13 This was a windfall for the leather industry. Whereas hunger and dire poverty drove desperate cattle owners to sell their cows and oxen to butchers, a thought revolting to Hindu sensibilities even today. William Digby describes a scene he witnessed on a winter morning in 1876 in Sholapur, in which he observes:14

The Hindus were forgetting their prejudices, and the butchers were busy slaughtering the beasts that were literally brought to them for nothing.

The shortage of cattle in times of famine had a terrible spin-off in the form of increasing conflicts between cattle owners and chamars, which were traditionally resolved at the village level in a highly reconciliatory manner but were now held up as examples of the inherent inferiority of the native savages. Suddenly there were rumours of cattle poisoning in different parts of India and in one such instance, following the precedent set by a similar enquiry in 1854, R.D. Spedding, the Joint Magistrate of Gorakhpur, alleged Arsenic poisoning as the cause of cattle deaths and forced many Chamars to confess to a crime they possibly never committed leading to a flurry of arrests. Soon, the crime had acquired the status of legend with senior British experts like Norman Chevers referring to it as the “ancient crime” of cattle poisoning. In no time, Chamars were stereotyped as a criminal caste.15 The chamar is remembered as the cattle smuggler but was actually the scapegoat of a bigger plot where examples of culpability had no basis in proof, but the punishment meted out was death. Unusual things like the ghosts smuggle the cows etc were spread as rumors. The official records read “commiseriat cattle” which is nothing but a platitude for stolen.

The famines did not last forever but they had managed to set a new normal, both in terms of the demand for hides due to the expanded scale of production during famines as well as the psychological normalisation of cattle slaughter. In order to satisfy the bloated production capacity and swelling demand for Indian hides in Europe, the British government began to build municipal slaughterhouses, which also gave them supervisory control over the process of flaying, significantly improving the quality of hides.16 Meanwhile, the condition of chamars and other leather castes all over India kept getting worse, they were left with no choice but to transcend boundaries – of identity and location. In other words, some were lured into the new religion of Christ in exchange for trivial and short-term benefits and a large number moved to cities, an unintended consequence of which was the birth of slums. Dharavi, the mega-slum of Mumbai often romanticised in Hollywood portrayals, came up precisely on account of the mass migration of Chamars to work in tanneries owned by Bohra and Memon merchants.17

The blame goes to…

The breakdown of traditional social structures, abject poverty, mass migration, landlessness, the proliferation of urban slums, and cultural estrangement are all interrelated realities of colonial and postcolonial India that thoroughly exploit the Chamars and other similar caste groups, who had for ages lived with dignity under an innovative, decentralized, sustainable and stable (sometimes labelled by economists as stagnant) market economy with ecology at its core. The journey from primitive to modern has been disastrous for them quite simply because the modern industry with its pyramidal power structures, obscene accumulation of wealth by a few, and grounding in colonial legal principles is exploitative by design.

Strangely, nowhere in the discourse on the condition of Chamars in modern India are these obvious causal connections drawn. Instead, academia, media, and pop culture, as if by the force of habit, reflexively invoke the ‘evils of caste system’ to explain away the harsh economic realities of the global capitalist economy. Untouchability, which is a fuzzy concept, its definition varying from customary restrictions on free intermingling to a socially conditioned reluctance in interdining, is consistently brought in to show that the chamar communities have been systematically denied basic human rights by savarnas. In the annals of Balutedari, the adhikara of clearing out of the dead cow’s hide is of the Mahar. Dead animal hides and the indignity associated with having had to deal with it figures in the literature and stories of several post-independence ‘Dalit’ autobiography writers, a genre of literature that gave readers the confidence that they could know the reality of avarna castes in pre-modern India simply by reading anachronistic first-person accounts. While not setting out in any way to negate the validity of such authors’ experiences, for they were absolutely true of the times that they lived in, to get to the bottom of the issue, one needs to couple these lived experiences with other factual details that have never been looked at before, or as is probably the case, deliberately ignored. The fact when reflected upon makes it clear that, for the clearing out of the dead cow and its flaying the person received land, remuneration in terms of a grain share, participation and rights during festivals and monetary compensation for artifacts produced, the raw material for which was given to him for free.

To reiterate, Mahars were treated as the members of the “thorli kas” or first-order in the traditional system of importance of the profession.18 In terms of celebrations and adhikaras, the Pola festival where the Nandi bull is worshipped and processions are taken out to this day, the Mahars are an integral part of the multi-caste celebrations and entitled to the Naivedya of offerings made as part of the ritual.

At the very core of this multidimensional problem then, is the living cow. What makes it more complicated is that not only is it a resource to be exploited but a long-standing symbol of revered holiness. How the cow dies and what happens to it when it dies then becomes a sort of metaphorical symbol for the journeys of indignity to those that draw moral and ethical meaning from their attachments to the animal. In our research, we find the Indian society transitioning from a completely cruelty-free sustainable process that efficiently takes into account the recycling of animal carcasses to a cruel method of extracting leather from an animal that was treated, not so long ago, like a family member. This downfall is parallelly reflected in the economic sphere by a loss of independence of enterprise to a slave-like existence in the newly developing slums of leather industries like Kanpur, Mumbai, or Ambur. The change is so radical that that news of humans beings dissolving in chromium tanks have to be kept away from the mass media news cycles, international journalists have to go in incognito to abattoirs in Kanpur to document the terrifying conditions of the factories. NGT reports of the dangerous levels of toxic slurries being emptied into the Ganga and its polluting effects on the lives of the workers have to be reduced to just a formality because implementing them means a shock to the existing status quo, in which every participant is aware of its malignant nature but each one is ironically powerless to do anything about it.

This radical shock to the system needs deeper sincere studies that seek answers to uncomfortable questions that have been contemptuously brushed aside. Why were cows being smuggled (and still are today)? How big was the smuggling if the entire British army was relying on Indian leather for its needs during both the world wars and exporting surpluses to the Americas? What is the basic structure of an industry where billions of dollars worth of raw material is actually free because most of it is stolen? Was the cow protection movement triggered by the sudden loss of cattle? What is the relationship of cow slaughter with ecology? Does the vanishing of cattle intensify the tragedy of famine? Does it also affect starvation indices during a famine? What is the unforeseen effect of the shortage on other spheres of village life that depend heavily on cow dung as fuel, fertiliser, and sanitiser?

The illusion of progress that undergirds the rhetoric of the modern global economy blindsides the privileged sections of society into believing that all would be hunky-dory with the world if only the vestiges of a primitive and barbaric past are wiped clean. This is not just a naively optimistic bias but a false consciousness artificially kept alive by powerful vested interests that define modernity itself – multinational corporations, nation-states, flesh trade mafia, arms lobbies, human rights industry, etc. It is interesting to note here that the trade route for leather put in place during the British regime works even today albeit many times more efficiently. Market regulation, the new whip to lash the subaltern with, is what manages to keep the ‘Dalit’ labourer underpaid, the Muslim boss as the keeper of most of the profit, and the Gora Sahab and madam capable of keeping their closets stocked with multiple pairs of jodhpurs and boots and belts that they can buy at a fraction of the real cost of these items. This is slavery in a new guise. The brunt of this abuse is borne by the Chamar but the savarna, who is nowhere in the picture in the chain of this abuse, is an easy scapegoat while the demon of colonialism is far from dead. The antidote to a structural Raktabeeja is digestion, and not the unimaginative approach of slaying it. Do we have the stomach for it?

References

1 Hutton, Magdalene and Shafahi, Maryam: ‘Water Pollution Caused by Leather Industry: A Review’

2 Gallagher, Sean: ‘The Toxic Price of Leather’ (video documentary)

4 Hoefe, Rosanne: ‘Do leather workers matter?: Violating Labour Rights and Environmental Norms in India’s Leather Production’

5 Various; Intersections Socio-Cultural trends in Maharashtra

6 Kulkarni, A.R.; The Indian village with special reference to medieval Deccan (Maratha country): General presidential address

7 Orenstein, Henry; Exploitation or Function in the Interpretation of Jajmani

8 Sujatha, V.; Leather Processing: Role of Indigenous Technology

9 Sinha, Sanjay; Economics Vs Stigma: Socio-Economic Dynamics of Rural Leatherwork in UP

10 Singh, Mahesh Vikram; Social Status of Artisans in Early Period of Indian History

11 Ibid

12 Roy, Tirthankar; Traditional Industry in the Economy of Colonial India

13 Ibid

14 Ibid

15 Mishra, Saurabh; Of poisoners, tanners and the British Raj: Redefining Chamar identity in colonial North India, 1850–90

16 Roy, Tirthankar; Traditional Industry in the Economy of Colonial India

17 Ibid

18 Fukazawa, Hiroshi; Rural servants in the 18th century Maharashtrian village—Demiurgic or Jajmani system.

Leave a Reply