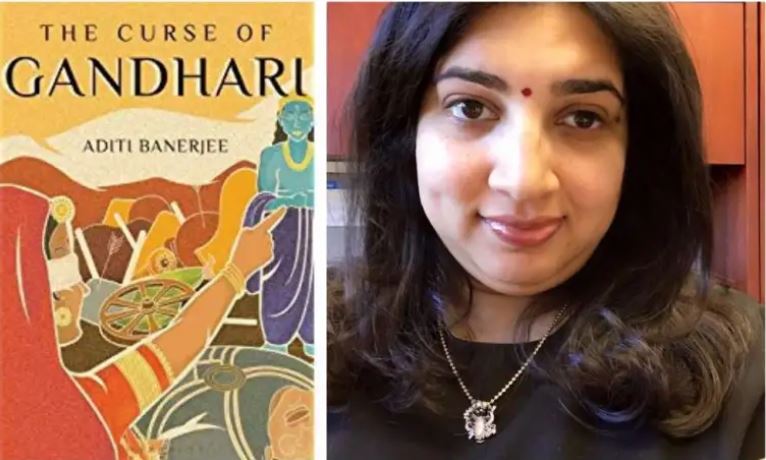

Aditi Banerjee’s work is the most nuanced and sensitive depiction of Gandhari I’ve come across. Presenting the events of the Mahabharata saga from Gandhari’s perspective, we witness her interactions and relationships with the central characters in all their complexities: the good, the bad, and the ugly. The prose is written in an almost poetic style with many philosophical and psychological insights dispersed across the book and uttered by key characters at key moments.

The Plot:

The narrative across the book is neatly divided into 2 sections: The present and the past, both of which are narrated from Gandhari’s point of view in the third person. It switches between Gandhari’s present, the Vaanaprastha stage of her life, and the distant to the not-so-distant past: events leading up to the Kurukshetra war beginning right from Gandhari’s girlhood. We learn of young Gandhari being raised with many brothers and tutored by her astute father, Subala. He trains her in all matters of governance, statecraft, and espionage. Gandhari blossoms under his tutelage and training and consequently, she attracts the attention of the Kuru clan for a boon promised to her by Lord Shiva. A boon that would grant her 100 sons and thereby ensure the continuity of lineage of any man she marries. Bhishma, a scion of the Kuru clan approaches her father to ask for her betrothal to the son of the family. Gandhari is overjoyed at first, only to later realize that it is not the pale and brave Pandu but the blind and feeble Dhritarashtra to whom she is being sought for! Shocked though her father is, he eventually agrees to the proposal amidst her brother Shakuni’s violent outbursts, vehement opposition, and Gandhari’s own reluctance. Despite her misgivings, Gandhari then takes her famous vow during the marriage ceremony. A vow to deprive herself of sight just as her future husband has been deprived of it since birth and she promises to be a devout and virtuous wife. This she ensures by blindfolding herself permanently with a strip of cloth.

Life at Hastinapur proves to be uneventful for Gandhari as she is more or less relegated to babysitting Dhritarashtra who is far more dependent on her than she’d imagined. She receives no opportunity to put her talents and skill sets to use although her initial interactions with her Grandmother-in-law, Satyavati, and her son Dvaipayana offer some comfort and consolation. The reader is privy to multiple events of the Mahabharatha unfolding from Gandhari’s perspective. These range from Kunti’s arrival and upstaging of Gandhari to Pandu’s subsequent withdrawal into the forest with his two wives, Gandhari’s long drawn out pregnancy and the birth of her children amidst many ill omens, Pandu’s death and the arrival of the Pandavas and many more episodes. It culminates of course in the terrible Kurukshetra war with its violent resolution and painful aftermath.

Some prominent themes include:

- Maternal Affection Gone Astray:

Gandhari has always been remembered as a doting mother who would spare no effort in ensuring her children’s wellbeing. Her intense maternal affection never wavers throughout the entire sordid saga. Right from the start, she refuses to abandon her firstborn despite a flurry of ill omens and against the wise counsel of the family elders. The son is deemed to be one who will wreak widespread destruction and annihilate the entire Kuru lineage. Many see her ‘blind ‘ love as a fault and criticise her for constantly giving into her children’s unruly desires, raising them to be a boisterous lot, and failing to impart the wisdom and guidance that Subala had given her. Whilst growing up, her sons constantly quarrel with the virtuous Pandavas with her eldest Duryodhana even going so far as to resort to vile forms of retaliation. It culminates in his conspiring with his brothers to murder Bhima. Throughout all events, Gandhari either refuses to believe what is happening in front of her eyes or stands silent. Although she never loses her sense of righteousness nor her ability to discern Dharma, she becomes increasingly powerless against her son’s acts of evil. Things come to a head with the disgraceful disrobing of the virtuous Drapaudi. Unable to rely either on her husbands or the elders of the Kuru court to protect her modesty, she seeks refuge in the one and only protector, Shri Krishna Himself. It is during this miracle that Gandhari finds herself being tested (unbeknownst to herself). She is temporarily granted the gift of sight that is limited to only glimpsing the Supreme Divine, Shri Krishna Himself. She sees Him look at her enquiringly before shifting his gaze in anger to Her wicked sons. It is then the wise Gandhari falters and fails. She makes a sudden but slight movement to protect her sons from Krishna’s (potential) anger and in doing so fails to act in accordance with Dharmic righteousness. This was her test. Ideally, she should not have attempted to protect her sons given that she stood silent during Draupadi’s humiliation. At the end of the book when she berates him for his role in bringing about the war, Shri Krishna gently reminds her that He gave her sons many a chance to redeem themselves and re-embrace Dharma. They failed to do so. To some extent, this equally applies to Gandhari herself. She too had multiple chances. Even towards the end, when war seems imminent, Gandhari is offered one more chance to prevent the destruction. Duryodhana is on the verge of suicide after having been humiliated in battle by one of Arjuna’s allies. She is called on by Karna and requested to beg him not to end his life. On the other hand, it is the opposite she contemplates, i.e. keeping her silence and letting him go ahead. It would simplify so much and prevent much further carnage. Unfortunately, his tears and despondency move her strongly and she succumbs to her maternal instincts. She entreats him to live and in doing so gives up another chance to act in accordance with Dharma. Once more she lets her blind attachment to her sons sway her better judgement. - Gandhari’s complex rivalry with Kunti :

If ever there was a complex relationship in a saga of complex relationships, then this is it. As sisters-in-law whose sons went on to become each other’s sworn enemies; to say their connection to one another was strained, would be putting it mildly. ‘Equal parts enmity and equal parts empathy’ would better describe it. Given that Gandhari had initially envisioned herself as Pandu’s wife and always retained a soft corner for him, one can hardly expect her to welcome Kunti as she had been supplanted by her right from the start. Barely married to Dhritarashtra, she was eclipsed in prestige by the new daughter-in-law of the family. Despite being her senior in age, she would never be the more renowned queen given that Pandu’s sons were the ones next in line for the throne. And yet the two women share many similarities. Both are exemplars of duty and devotion, perform pious austerities to attract boons and blessings from Devas and Rishis, both have unhappy marital lives and often find themselves being placed in circumstances beyond their agency.

The book neatly depicts the nuances in their complex relationship – the good, the bad, and the ugly, without reducing it to ‘Two jealous sisters-in-law’. This is a tired old trope that was a mainstay in popular ‘Saas-Bahu’ sagas of the late 90s-early 2000s and the author wisely sidesteps that.

The book also touches on a lesser-explored dynamic between Gandhari and another central character – Drapaudi. Gandhari sees her as the daughter-in-law she wished she could have been in her youth. Her regalia, queenly demeanour, and composure under great duress and humiliation (particularly during the disgraceful disrobing spectacle carried out by Duryodhana and Dushasana). Gandhari simultaneously admires and envies her while remaining (mostly) mum during the sorry spectacle. - In Conclusion:

The author takes creative liberty by including a final chapter that is absent from the original text. Some may criticise it as ‘sentimental’ but I think it was a creative gamble that paid off. This denouement is a scene in which she imagines one last conversation between Gandhari and Shri Krishna. I won’t give spoilers; suffice it to say that it’s very well executed. I sense strands of the author’s own Bhakti and Sadhana’s insights in some of these passages. A neat and hopeful ending.All in all, this is an excellent book and one that’s well worth re-reading now and then. Heartily recommended.

Final Rating: 5/5 Stars

Leave a Reply