General GD Bakshi is not just anyone. After retiring from the army, he became a well-known television face applying his military knowledge both to the contemporary political debate and to classical cultures, e.g. the strategic aspect of the Mahabharata war. Everyone in India knows the story that on his very first day in service, in 1971, he was called to fight in the Bangladesh war,– a Just War if ever there was one. It showed that sometimes, going to war is the lesser evil: in this case, it was the only practical way of stopping a Pakistani genocide that was making more victims per day than the whole Indian military intervention made.

Mahabharata for strategists

It is at several conferences on the Mahabharata, the classic on the theme of Just War (Dharma Yuddha), that I first met the general. There, his cold strategic look at the story was quite an eye-opener to historians like me, but a bit of a cold shower to more religious types.

For pious denouncers of arch-villain Duryodhana, whose refusal to give even five villages to the rival Pandava brothers counts as the proverbial example of unreasonableness, please consider the strategic angle. After their wedding with Panchala princess Draupadi, the Pandavas might well want the fusion of the Bharata kingdom with Panchala, meaning the conquest of the Bharata kingdom, and in that project, the five villages would acquire tactical value as offensive outposts.

Even Krishna, a common object of devotion, was not spared. As we know, Gandhari, mother of the slain Kaurava brothers, curses him as the real culprit of the war. After all, he as a prince of the Yadava tribe has egged the two sets of Bharata princes on to fight and massacre one another. Not surprisingly, it is the non-Bharatas who profit, with the throne of the Pandava capital Indraprastha falling to a Yadava prince, viz. Krishna’s own grandson. So, though idealized and ultimately even divinized by the epic’s pious editors, Krishna may originally have merely been a calculating strategist mindful of the Yadava tribe’s self-interest. That at least is what the naked strategic data suggest.

It does not come as a surprise, therefore, that regarding the independence struggle too, General Bakshi brings down a pious legend featuring a canonized Saint.

Who achieved independence?

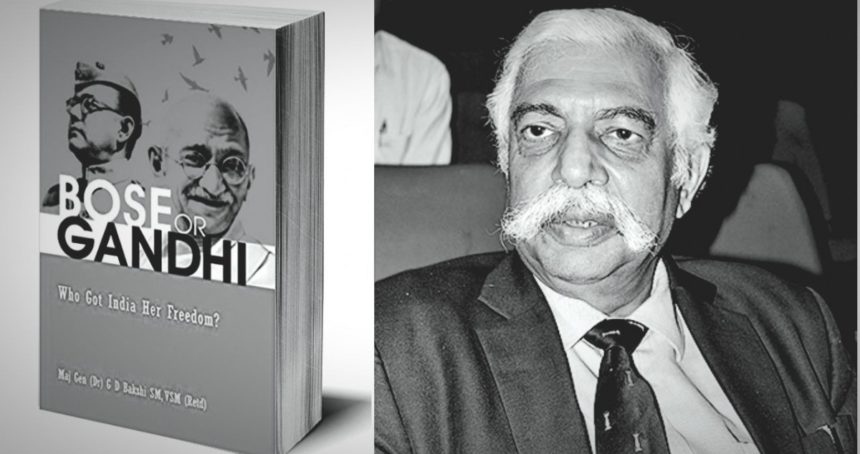

In the present volume, Bose or Gandhi, Who Got India her Freedom? (Knowledge World/KW Publications, Delhi 2019, ISBN 978-93-87324-67-1, 216 pp.), Bakshi takes on an important topic from recent history: what factor was decisive in achieving India’s independence? The received wisdom, both in Congressite India and internationally, is that this historical achievement was the result of Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent agitation. But was it?

How do you wrest the sovereignty over a Subcontinent from a world power? The British-Indian empire was built on a bluff and on the dividedness of the population against itself. This was not threatened by the initial Congress movement, which was just a talking shop of lawyers pleading for native interests within the British empire. By contrast, it had really been threatened by the Mutiny of 1857, when different communities rallied around the Sepoys (Sipahi, native soldier in colonial service) and came together to revolt against the British. And this gives the gist of Bakshi’s narrative already away: the British were afraid of military revolt, particularly by the native mercenaries on whom they counted to uphold their imperial edifice, not of pious discourses and slogans.

However, the General does give the Mahatma a part of the honour. No doubt, the shift of Congress activity from lawyerly negotiations to agitation at the mass level was Gandhi’s achievement. He popularized the Freedom Movement. This is undeniable, but the point is: it is not what made the British decide to pack up and leave.

Look at it in more detail than is done in, for example, Richard Attenborough’s propaganda movie Gandhi. The Mahatma’s last campaign was not the camera-savvy Salt March or other events from before the Government of India Act 1935, the reform with which the British managed to renormalise the situation and regain control over political developments. It was the Quit India movement started in August 1942, which was a failure in every respect.

First off, it was based on an assessment of the world situation that seemed plausible in 1942 but turned out to be wrong: that the Japanese would win the war and chase the British from India. In that event, India would be in a better position if it was an independent Asian nation rather than a British colony (though, what about the independent Republic of China?). Second, it created profound dissensions in Congress, which was mostly reluctant to embark upon this adventure. Strategically, the British were at war and on the defensive, so they would not pull their punches in the repression of any “disloyal” agitation; and morally, many Congressites, such as Jawaharlal Nehru, were on the British side in that war. Indeed, it is mostly Nehru’s speech against Quit India that made the British decide he was essentially “one of us”, so that they started treating him rather than Gandhi as their Congress contact. Third, though intended to be non-violent, the movement soon lapsed into violence, depriving Gandhi of his moral high ground. Fourth, the British put the movement down brutally but efficiently. Fifth, the Congress leaders were imprisoned and neutralized while their rival Mohammed Ali Jinnah remained free to enlarge his influence. Sixth, when they were released, they were demoralised and had lost credibility. Especially Gandhi, chiefly responsible for the movement, had been cut to size; he only regained his place in history by his martyr’s death.

After the Japanese capitulation on 15 August 1945, the Freedom Movement as such was nowhere to be seen. Paul Johnson and other historians who have lapped up the official version, with the Mahatma as the main motor of decolonization, write that if the British themselves hadn’t been kind enough to leave, it is unclear how independence could have come about, as the native dynamic for it had petered out. But they have been tutored to be oblivious of the one factor that dramatically revived the Freedom Movement within weeks: the return (in chains) of the soldiers of Subhas Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army (INA)/ Azad Hind Fauz.

The INA

After the war had broken out on 3 September 1939, India’s politicians had to choose their camp. Jinnah’s Muslim League automatically sided with the British, and so did Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, mainly for tactical reasons: that way, numerous Hindu young men would get military training and experience. The sympathies of Congress largely lay with the British, but they fell out over a procedural matter: the Viceroy had declared war without first consulting with Congress, their partner in administering India’s partial self-rule. So, while its political rivals were earning the Brits’ gratitude, they remained on the sidelines, never the best way to make the most of a war situation. The Communists, meanwhile, opposed the “imperialist war”, blaming it after the Soviet example on the “bourgeois democracies” France and Britain, rather than on Germany; it is only after the German attack on the Soviet Union that they made a U-turn, supporting what had become a “people’s war”.

One significant leader remained on his own: Subhas Chandra Bose, born in Cuttack in 1897. He belonged to the Congress’s Left-wing but had been ousted as Congress president by Gandhi. As a response, in 1939 he founded his own party, at first intra Congress, the Forward Bloc. It would remain in existence after the war and be part of the Communist-led alliance that governed West Bengal for decades. In spite of being under house arrest in Kolkata, he fled to Afghanistan in January 1940, and thence to Moscow, where he hoped to get cooperation for military action against Britain. He was told that the Soviet Union was not at war with Britain, but their temporary ally Germany was.

Ideologically this did not pose a problem: Bose had always believed that India would need a few decades of dictatorship, which would administer the best elements from both Communism and Naziism. (Mind you, this is my own addition to the background sketch, General Bakshi purposely leaves the ideological aspects out of his consideration: some readers might object to Bose’s ideological choices, yet that doesn’t alter his strategic role in forcing the transfer of power, the actual topic of this book.) He had already lived in Austria intermittently in 1934-37 and even had a wife and baby daughter there. So he was brought to Germany, where at once he could raise an Indian army with 3000 Indians from among the British prisoners of war caught in Dunkirk, with the privilege of only fighting British enemy soldiers.

It is in Germany that Bose received the title Netaji from his men, “revered leader”, roughly the translation of Führer or Duce. It was in Hamburg, during the founding of the German-Indian Friendship Association, that his soldiers and well-wishers stood to attention for the first time for Jana Gana Mana as the national anthem. While Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop had humoured him with vague assurances of support, Bose’s meeting with Adolf Hitler was a cold shower. Hitler expressed his belief in the rightness of British (“Aryan”) colonization. When Japan entered the war in December 1941, and asked Germany for Bose after taking hundreds of thousands of Indian prisoners-of-war in Singapore, Germany transported him by submarine in early 1943, and he was now welcome to lead some 40,000 soldiers in the INA. This force had already been founded by expatriate Indians, notably by Ras Behari Bose, but now it needed a credible leader, and Subhas Bose was the right man for the job.

Bakshi informs us cursorily that from abroad, Bose also did what he could to contribute to the struggle within India, including the Quit India movement. Alas, the delivery of arms and other material which he arranged for, was often sabotaged by unreliable agents, and remained without sizable effect. His main claim to fame was and still is the INA.

Unfortunately, in military respect, the INA came too late on the scene. It never controlled more of India than the Andaman and Nicobar islands and some border areas of the Northeast. When it seriously besieged the Northeastern cities of Imphal and Kohima, the momentum of the Japanese advances had passed, and the British-Indian army could take care of it. The INA still fought some battles against the British forces in Burma, but its historic chance in India had passed.

Bose’s afterlife

In the chaos of war’s end, Bose is said to have died during an aerial accident in Taiwan. That at least is the official version, but since the beginning already, it has been doubted. It was based solely on the eyewitness testimony of a surviving companion and lieutenant of Bose’s, whom British intelligence immediately suspected of merely having thereby carried out orders from Bose himself, who this way had staged his own escape. Bakshi is not into writing a biography here, so sensation-hungry readers will be disappointed to find that he merely gives a nod to Anuj Dhar’s eye-catching book India’s Biggest Cover-Up (2012), which argues that Bose did indeed escape to the Soviet Union, where he was put in custody. Nehru was good friends with the Soviet leaders (to the extent that when in 1962 the Chinese, angry with Soviet manoeuvres on the Manchurian borders, decided to pin-prick the USSR, they invaded India), so it sounds plausible that they did his bidding, which was to keep Bose out of reach of India. Bakshi doesn’t evaluate such questions, because no matter what Bose’s ideology or personal destiny, one solid fact deserves to be established now beyond future doubt: his decisive role in achieving independence.

Indeed, all speculations on Bose’s personal life are dwarfed by the immediate effect of India’s exposure to what the INA had meant. In autumn 1945, a large part of India’s population immediately sided with the INA veterans upon their return (in chains) to India. The British gradually released the ordinary soldiers in batches, which already had a palpable effect, for as Nehru observed, these men were hard as nails and hated British rule. The eye was mainly on three top defendants. Their trial, in the Red Fort, was meant to send a message to the Sepoys never to be disloyal again. Coincidence would have it that they were a Hindu, a Muslim and a Sikh, which came in handy for the Congress narrative of a pan-Indian unity. Congress leaders buried their one-time diatribes against the INA and offered to defend them in Court.

From the Empire’s perspective, the trial really backfired. The people’s mood proved not to be just a fleeting sympathy but threatened to become a rebellion. A large part of this book holds the British military correspondence of autumn-winter 1945-46 against the light. It becomes abundantly clear that the British top brass, especially Viceroy Archibald Wavell and Commander-in-Chief Claude Auchinleck, were in a state of panic. They had received reports from the provinces, including their main recruiting-area Panjab, that their colonial troops could no longer be relied upon. Every Indian had become a nationalist, galvanised by the presence in India of thousands of Bose’s soldiers. Nobody was willing to accept the punishment which the British would normally have given to leaders who had taken up arms against the King-Emperor.

In proportion to the gravity of what from the British viewpoint was a crime, they should have been sentenced to death. Sensing that this would only trigger a revolt, Wavell and Auchinleck arranged for a reduced sentence to transportation for life, which moreover was at once commuted to a token prison sentence. To prevent any incipient unrest, they made sure that this decision was immediately communicated to the public. It became a staged trial with the outcome determined by extra-judicial considerations, a “show trial” but this time not to the detriment of the defendants, thanks to the emerging anti-British power equation in society.

But this was to prove insufficient, and the real gravity of the situation was yet to come to light. The British troops sent to India for the war against Japan were being demobilized and repatriated. More than before, the Empire was now dependent exclusively on the Sepoys. And in early 1946, in a number of Naval units, these soldiers bound by oath to the King-Emperor rose in revolt. This was the decisive pillar under the imperial structure: if it crumbled, it was curtains for the Empire.

A combination of repression and of moral pressure by Congress, committed to non-violence but also mindful of its own privileged relation with the British, managed to put down this Naval Mutiny. But only for now; the British rulers realized that they might not be so lucky next time. So they called on London to announce a date for independence. The last Viceroy, Louis Mountbatten, arrived in March 1947 with the one-point programme of organizing the transfer of power.

Other considerations

What Gandhi had not achieved in decades of campaigning, Bose’s INA achieved posthumously in less than two years: making the British to quit India. And this, in fact, without firing too many bullets: if you radiate power, you often don’t have to use it. The court historians have always downplayed the role of the INA and attributed the merit for the achievement of independence to the Mahatma. But this legend was gainsaid by no less an agent than the British Prime Minister who effected the transfer of power, Clement Attlee. During his visit to India, he was asked what considerations had made him decide to decolonise India. He cited the military equation with the increasing unreliability of the troops, and as for Gandhi’s role, in his estimation, it was “m-i-n-i-m-a-l”.

As this book was going to the press, it so happened that official India was finally extending recognition to the INA. A handful of surviving veterans, nearly 100 years old, were driven in an open jeep in the Republic Day parade. When Westerners hear of Bose, they consider him as a mere Axis collaborator. For Indians, he is first of all a national hero, and the cruelties which made the German and Japanese war machines infamous, were not the doing of their Indian army units. These soldiers did not join their units to fight for some German or Japanese Empire, but for their own Motherland.

In India, some had fought with the British, some against them, some had taken different positions in succession, some had tried to stay on the sides, but at war’s end, it was agreed that everyone had done it for the best of Mother India. In some cases, that was a flattering assessment, but precisely in its flawed truthfulness, it showed the generosity of spirit of Indian patriotism. No one’s war record was scrutinised, for in India on 15 August 1945, the Second World War was really over.

Nationhood

In his introduction and his last chapter, General Bakshi also explores issues of nationhood, India’s unity and integrity, and India’s status as a civilisational state. It is interesting to see how a no-nonsense patriot thinks about the current political contentions.

Of course, he rejects Gandhi’s and to some extent Nehru’s option for a defence without military strength. It is a state’s prime duty to protect its citizens, and this requires an army. As a NATO slogan from my young days said: “Peace through strength.” This is a truism, followed by most state leaders in history, and it is not India’s major claim to fame that its national Saint flatly denied it.

India’s integrity demands that the system of caste-based and communal reservations is phased out. This system has been instituted by the British as part of their policy of divide and rule. Since the Government of India Act 1935, and expanded in the Constitution of India 1950, it divides society in birth groups. Then it was in the name of “Imperial Justice”, now it is in the name of its more modern-sounding equivalent, “Social Justice”.

That this became the central value of India’s Constitution, and not “Liberty” or so, provides an interesting parallel with the contemporary West, where “Social Justice” has become the justification for the craziest demands, and indeed for an expanding system of mostly birth-based (racial, gender, etc.) quota. Yet in India, this did not originate in Marxist or quasi-Marxist sources like Antonio Gramsci or the Frankfurter Schule, but in another system of colonial domination, viz. British colonialism. The effect is nonetheless the same: endless dividedness, a variation on the Marxist model of class struggle.

It has logically been the Left that made itself the heir of this British system of reservations, and now champions quota schemes such as job quota for Backward Castes and the 2008 Right to Education Act. Today, little difference is left between the quota philosophy in India and in the US, except for the Indian oddity of the caste system. Bakshi proposes to make short work of this system and replace it with economically-based reservations. These would automatically favour the lower castes, which have more poor people, except their “creamy later”, those who have worked themselves up yet keep on milking the caste-based system and now have the most interest in perpetuating birth-based reservations. With the introduction of the Aadhaar Card, a kind of identity card including one’s financial-economic data, this is now technologically possible.

But there, we have crossed over to the issue of “decolonisation”. India wants to get rid of the remnants of colonialism, and one of these is the reservation system. The philosophy was that the benighted natives were naturally unjust and that the colonizer was needed as an impartial arbiter. Later, the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty appropriated that role to itself. By now, India is mature enough to shake off such colonial-age solutions.

In parallel, another relic of the colonial age and its immediate aftermath is the lionization of Mahatma Gandhi as the bringer of Independence and the concomitant downplaying of Subhas Chandra Bose’s contribution. That motivated legend is, after this book, no longer sustainable.

Leave a Reply