When we perceive Bharat as a civilization and do not restrict her to the concept of a modern nation-state, we unfold various dimensions of her continuity and mutual exchange with other cultural lands. And when we succeed in accomplishing this national devoir, we begin to accept that Hinduism, as a converging matrix or as a larger cultural fold, can be the Daruka (charioteer) of the world’s Nandighosa (chariot), to direct the latter on a victorious path. The description of Indian Civilization and Hinduism has been rightly framed by Bernard Cohn in his book ‘An Anthropologist Among The Historians And Other Essays’, where he regards Indian Civilization as multiple orderings of diversity and Hinduism as a body of distinctive historic tradition.1

Apart from India, another land of people which outshines in case of a mode of style and which represents a harmonious blend of simplicity, art, and nature love, just like Bharat, is Japan. Bharat’s and Hinduism’s direct penetration into the land which unites people through the blossoming of cheery flowers was with the introduction of Buddhism in Japan in the 6th century. The visit of an Indian monk Bodhisena in 752 AD to Todaji Temple, the earliest documented direct contact with Japan2, introduced Hindu and Buddhist views to Japanese cultural and political life and enriched the latter, especially in the area of religious iconography, traced through the temples in Japan.

Hajime Nakamura, a Japanese scholar, believes that the Mahayana Buddhism of Japan has more Hindu influence than the Mahayana Buddhism practiced in other parts of the world.3 Various Bhartiya customs were introduced in Japan accompanied by the flourishment of Buddhism. As per Hajime Nakamura, rituals related to cremation, ancestor worship, offering water, rice cakes (pinda), and incense to the deceased soul of their ancestors, were made familiar to the Japanese.4 But, historically, before direct contact, the Japanese had divided the world into three parts. Japan as Yamato, China, and Korean Peninsula as Kara and India was known by the name “Tenjiku” with whom they had indirect contact.5

Another important point in history is that during the rule of Prince Shotoku Taishi, in 593 AD, Buddhism was ‘nationalized’ in Japan. But even after an ordinance related to Buddhism and Confucian teachings was promulgated, Buddhism never achieved the status of a mass religion as it got restricted to the elite class. It was only after the arrival of Bodhisena that Buddhism blossomed. Later on, the policy of self-seclusion was adopted by the Japanese rulers to maintain cultural purity. This policy of self-seclusion from the foreign lands hindered the full-fledged interactions between the two cultural lands. This policy ended in 1869 with Meiji Restoration. The reopening of Japan with other cultural lands, stimulated the visit of Japanese travelers and scholars to the Buddhist sites in India with the objective to imbibe the core and true teachings of Gautama Buddha (Sakyamuni). Kitabatake Doryu, Shaku Kozen, and Shaku Sen are few among them.

The religious and cultural ties between both the lands, built because of centuries of interexchange, can be explored through various practices which have certain points of commonality to be arrived at. One such practice in Japan is “Hara Hachi Bu” which means ‘eat until you are 80% full’ or “stop eating when you are 80% full”. This practice originated in the city of Okinawa, one of the world’s blue zone regions. This is an ancient practice to prevent people from overeating and follow healthy digestive practices. Jainism, considering it as under the larger fold of Hinduism, prescribes “Ratri-Bhojana Band” which means not to eat after sunset. Ratri-Bhojana Band is important because the food eaten at night time does not get properly digested since the digestive system is less active and the metabolism rate slows down during these night hours as we do not indulge in any physical activity which helps in digestion. The second similar prescription attached to the importance of healthy living is the preference for the eating of “satvik” food which represents purity, harmony, and compassion. It includes fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grains, foods grown above the ground and receiving the positive energy of the sunlight, and includes the restriction on overeating.

The union of Bharatiyata is mainly represented through Hinduism, and the Japanese culture can be detected under the aegis of dining practices of both. The Japanese families eat their meals while sitting on a cushion placed on the tatami floor (a reed-like mat), in a position similar to Sukhasana/cross-legged, facing a low dining table. They believe it helps in easy digestion as when we bend forward to have food and then revert to the original position to swallow the food or muscles in the abdomen are strengthened which in effect prevent bloating. This is followed by a gesture of gratitude. Before eating, Japanese people say “Itadakimasu” which means, ‘I humbly receive’ and extends kind respect to those who prepared it and this is accompanied by putting both hands together like namaste and bowing slightly in the front.

In Hinduism, we also have “Acharas” associated with meals, which outshine the Japanese gestures/etiquettes. We have the code of conduct or acharas for, before a meal, during the meal, and after the meal. We offer “Naivedya” to the deity as a symbol of being thankful to him. We pray to God and chant his name while consuming food and develop an emotion that the food is God’s prasad and this act is termed “Yadnyakarma”. We sit on a wooden seat cross-legged/Sukhasana to improve our digestive process and body flexibility. Thus, all these acharas have some replicas in the Japanese dining etiquettes.

Analysis of civilizational imprints can never be complete without the study of “Ramayana”. As it has been perceived differently across South and Southeast Asia, it can serve to imagine unitary Asia. In Japan, the story of Ramayana is depicted in two major forms- literary and visual. Sambo Ekotoba (11th century) and Hobutsushu of 12th century contain the tale of Ramayana. The audio-visual form to display Ramayana delightfully includes the dance form of Bugaku and the Gagaku music. Thus, Ramayana represents the intercultural exchange.

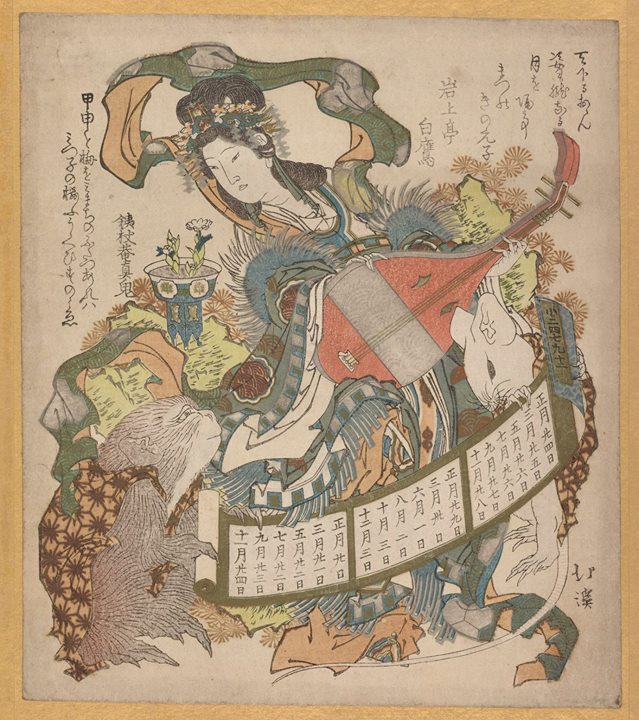

The bond between Japanese culture and Hinduism gets portrayal in the similarities between Hindu gods and goddesses with the divine figures of the “Shinto” religion. One such winsome example is “Benzaiten”. Benzaiten is a Shinto Kami (Shinto Deity) who represents the flow of music, dance, knowledge, wealth, and beauty, often depicted holding a biwa (a traditional Japanese Lute). She is based on the Hindu goddess Maa Saraswati. Benzaiten with the other Shinto deities reflects the influence of Hinduism (including Buddhism) over the Japanese religion of Shinto.

Another crucial example is of the Vedic God Agni. Agni, since Vedic times, symbolizes perfection and purification and has always been a mediator between the person making the offering and the God in a sacrificial ritual. In Shingon Buddhism of Japan, Ka-ten has also the same characteristics and manifests enlightenment achieved through the burning of desires and shedding ignorance. The resemblance between Shiva and Acala (a Shingon deity) can be also be drawn. Both signify the destruction of ignorance depicted through the Trishula and Sword of Shiva and Acalanatha respectively.

Similarities can be traced through the festivals of both lands. Tiruvadirai is the festival dedicated to Lord Shiva in the Tamil region of India. Seven vegetable porridge with cooked sweet rice is offered to Lord Shiva in the month of Margali (between 15th December to 15th January). The festival of seven young herbs is also celebrated in Japan where seven-herb rice Porridge is offered to “Acalanatha”, a Japanese deity identical to Lord Shiva. The festival of Navratri, representing the strength and victory of the Shakti cult, is also identical to the Doll Festival (Jomi no sekku) of Japan, introduced in the 9th century.

Another refined example is Marayapaksa Sraddha. Pinda (cooked rice balls) are offered to the ancestors in Marayapaksa Sraddha. The Bon Festival of Japan also includes the concept of offering (dana), showing lamp (light), umbrella, and water, which takes place while performing Sraddha in India. “Sraddha is nothing but the stand on which the souls of the dead are enshrined as Shoryodana in Japanese”. 6

With the beginning of the 21st century, a new impetus to the Indo-Japan bilateral relationship was provided with the end of the cold war, and India’s adoption of the path of liberalization favored Japan’s involvement to re-strengthen the old civilizational ties. The “Global partnership between Japan and India” was established with the efforts of Prime Minister Mori and Prime Minister Shree Atal Bihari Vajpayee in 2000. Further at this juncture, “Confluence of the Two Seas, a speech delivered by the then Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to the Indian Parliament, is significant. Abe advocated the idea of “Broader Asia” and spoke of the Pacific and the Indian Ocean as the confluence of the values of freedom and prosperity.7 The transition from an earlier strategic partnership to the Special Strategic and Global partnership indicates a kind of qualitative up-gradation from both sides. From civilizational to the specific strategic partnership, reflects the interest of both the countries in strengthening democratic values, promoting stability, and not confining the relationship canvas only to a political and economic partnership, these aspirations can currently be seen in the participation of both India and Japan in Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD).

With the visit of Bodhisena, the establishment of diplomatic ties between both the countries and the recent up-gradation of bilateral relations to ‘Special Strategic and Global Partnership’8, we have shown to the world that bilateral relations can successfully be developed and sustained on the basis of cultural resemblance and the festival of Holi and the festival of Hanami (spring festival of cherry blossoming), can together gracefully be sculpted in a brawny relationship. The same can be unearthed in Hajime Nakamura’s quote- “India is culturally, Mother of Japan. For centuries it has, in her own characteristic way, been exercising her influence on the thought and culture of Japan”.9 Thus, we need to overcome the Orientalist and Christian missionary view of Indian Civilization and Hinduism and should perform the role of “Hinge groups”, who not only mediate up and down in multilevel hierarchical civilizational centers but between different civilizational lands as well.

References

- Cohn, B. S., & Guha, R. (1988). An Anthropologist among the Historians and Other Essays. Oxford University Press.

- Brief note on India-Japan bilateral relations. (2017, November). Ministry of External Affairs.

- History of Relations of Asian countries

- Khan, S. A. (2017). India-Japan Relations: Tracing the Cultural and Religious Roots. In Changing Dynamics of India-Japan Relations (pp. 1–7). Pentagon Press.

- Ibid, p.1.

- Sankarnarayan, K. (1998). Festivals and Faiths. In M. Yoritomi & I. Ogawa (Eds.), Traditional Cultural Link Between India and Japan (pp. 286–291). Somaiya Publications.

- “Confluence of the two Seas,” speech by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, at the joint session of the Indian Parliament, available at http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asiapaci/pmv0708/speech-2.html.

- Brief note on India-Japan bilateral relations. (2017, November). Ministry of External Affairs.

- India: Mother of Us All – By Chaman Lal p. 25

Leave a Reply