“The project is religious, strategic as well as hydrogeologically significant”, we were educated on Twitter about the benefits of the Char Dham Corridor Project. While we sincerely admire the clean-up carried out by the government after the 2013 floods, which has made the area around the shrine cleaner, prettier and more pilgrim-friendly, the Char Dham Project itself is far wider in its scope than the facelift and the building of protective structures. The project poses serious challenges to the very essence of the pilgrimage.

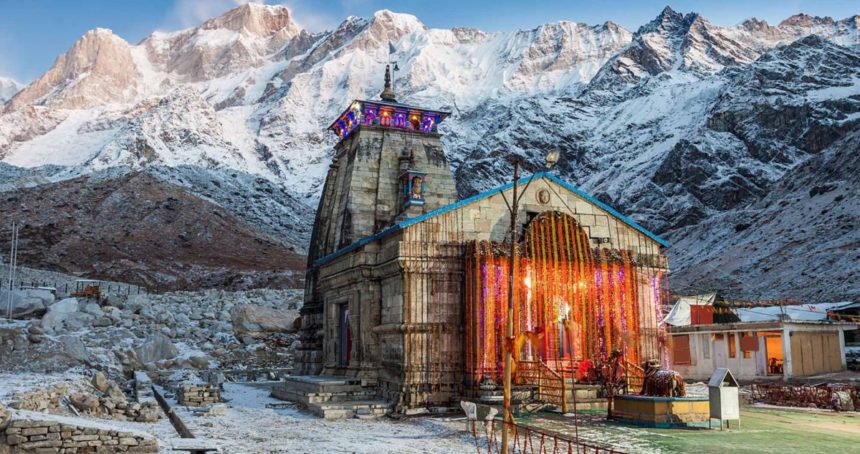

The debate, if we can call it that, started with the above two-minute video that brought attention to the overcrowding and the resulting threat to the sanctity of the Kedarnath shrine in Uttarakhand. A video that short is not meant to take a deep dive into the complexities of an issue or provide clear-cut solutions. Rather, it can be said to have done its job if it captures the attention of the viewers and successfully plants intelligent questions in their minds. But we realized soon after the release of the above video that questions may or may not be intelligent but can be very uncomfortable. The questions raised in the video triggered a massive overreaction from some people on Twitter, unfortunately not in the form of coherent arguments but naked emotionalism. They called us names like “Dharam ke thekedaar”, insinuated motives, questioned our intentions and some went to the extent of calling us agents of the Church. Thankfully, one of them wrote a long blog post, the abridged version of which was published in Swarajya. We are glad we have something to respond to. But do we actually?

It would be totally unfair to say that the article lacks information. Our grievance is that there’s more information than relevant. It is indeed a treasure trove for trivia gatherers looking to mug up facts about the 2013 flood and the eventual restoration work taken up by the government. We must also congratulate the author for having used some very beautiful images of the area to make his point. But sadly, by the time we reach the last paragraph, we are left wondering what that point really is. Nearly half the space has been devoted to explaining the causes and consequences of the 2013 floods. Having established his authority as an ‘expert’, the author goes on to make claims about the benefits of the restoration work on behalf of the government. He talks about the construction of ghats, retaining walls, guest houses, plazas, substations, sewage networks and so on. Moving on, he brings in temple purohitas and how the new housing takes a great financial burden off their chests and finally proceeds to point out the geostrategic importance of good roads in the area considering its proximity to China. These are all excellent points, but it is difficult to relate them to the issues raised by the video.

In passing, it is also worth mentioning that not all proclamations in the piece are rocket science stuff.

“Road widening and building new roads (read widened foot paths) are necessary as the earlier one had been completely destroyed in 2013.”

Indeed, roads are often built after they’re destroyed, whether it is in Garhwal or Mysuru. It should hardly come as a surprise for someone who places such immense trust in the Public Works Department. Be that as it may, we would like to curtail our instinct to point out more ludicrous statements and instead, summarize the mendaciousness of the entire blog post in a single sentence: It reduces the extremely nuanced debate on Ecology, Dharma and Development to a sycophantic admiration for the construction work around the Kedarnath Temple. Let it be clear that the video did not criticize the restoration work around the shrine but raised concerns about the exponential growth in footfall. The blog post is simply talking to the voices in the author’s head and we’d prefer not to intrude the privacy of his inner world.

Before we proceed to articulate our views on the delicate issues of Dharma and Ecology, we would like to take a small detour and direct the reader’s attention away from Uttarakhand and towards Odisha, where as a part of the State Government’s renovation package of Rs. 500 crore, an eviction drive around the Jagannath Temple at Puri is in the process of demolishing many heritage structures, some of them 900 years old, in the name of – wait for it – development. While “Dharam ke thekedaars” of the Indic Collective are running from pillar to post trying to get a stay order on the ongoing demolition in Puri, our good friend takes the opportunity to showcase his cluelessness again. He tweets with uncalled for glee:

What is happening in Odisha is not very different from what has happened in many shrines all over the country. Time and again, we have witnessed that the modern Indian State is not a reliable ally when it comes to civilizational issues. Bitter as it may be, the truth is that more often than not, the Indian State is found to be passively contemptuous or actively hostile to the interests of Hindu Dharma. Therefore, it goes without saying that when it comes to matters of religion, we are pretty much on our own and we need not take oaths of allegiance with any political person or party.

Nature, Deities and the nature of deities

We received repeated counsel from various Twitter personalities that while clarifying our position on the matter, we must stick to one item at a time – ecology or religion. This advice captures the bewilderment of the contemporary Hindu about reconciling Dharmic values with the pressures of modernity. To be clear, Dharma is ecology – that which sustains. The political animal who does not get this point is ironically playing out the script of the hated colonizers, in which they made a distinction between the nature-worshipping ‘tribals’ and the Veda-evangelist outsiders.

Animals, trees, rivers, and mountains do not just form a part of Hindu mythology but are an intrinsic part of rites and rituals too. The Sthala Puranas describe in detail the significance of the physical location to the form in which the deity manifests in a given shrine. It is in accordance with this very principle that women in their fertile phase of life are not allowed in the Sabarimala Temple while they are free to have the darshana of the same deity in other temples. Lord Ayyappa as the Naisthika Brahmachari in Sabarimala is not identical with the form of Ayyappa in the Achankovil Sree Dharmasastha Temple, where he is married to two women and has a son too.

Now, if we apply the same principle to Kedarnath, we will have to change the order of preference from the devotees’ rights to the deity’s preference. To know the preference of the deity, we will have to interpret the puranic stories associated with him. Kedarakhanda is a text that localizes the stories of the Shiva Purana to the region around Kedarnath, and not just the shrine – reinforcing the point we made earlier about the interchangeability of the shrine’s identity with its wider ecological setting. Pilgrims to Kedarnath often think of themselves as following the footsteps of Pandavas but how many of them pay heed to the narrative of Kedarakhanda, which speaks of their violent struggle to get to Shiva? As Luke Whitmore writes, “The darshan of Shiva in Kedarnath is the darshan of a deity whose face has turned away”, implying that he is a recluse whose attention demands struggle. Thus, the pilgrimage is meant to be arduous, uncomfortable and challenging in the extreme, even if the champions of modernity may want it to be like a picnic. It may be surprising to them, but it is rather obvious that ever-increasing footfall is not what the Lord of Kedar fancies according to the descriptions in the Shastras.

Ecological concerns

As mentioned above, the religious view of Kedarnath does not think of the shrine as constrained within the four walls of the temple. Rather, it sees the whole area as a single unit pervaded by the powers of Shiva and Shakti. Thus, any damage to the environment is, in fact, an assault on the deity. The development project that threatens the ecology of the region most is not the limited construction work around the shrine, a red herring invented by the fanboys but the much-celebrated Char Dham Mahamarg Vikas Prayojana (Char Dham Highway Development Project).

The Char Dham project was conceptualized in the year 2016 as a tribute to the victims of the Kedarnath flash floods in 2013. It proposes to build a road network of about 900 kilometres from Rishikesh in the south to Mana in the north. It will include 2 tunnels, 15 big flyovers, over a hundred small bridges, more than three thousand five hundred culverts, and twelve bypass roads. Ignoring the fact that the construction is taking place in an eco-sensitive zone, the government has divided the project into 52 parts so as to bypass the statutory requirement of obtaining environmental clearance from the competent authority.

[Landslide on Badrinath highway. Picture courtesy: ANI (Sep 2019)]

The government has not made adequate arrangements for the muck that has been generated due to the project which has led to its dumping into rivers. The deposition of muck into rivers has hindered their flow, accelerating the drying up of rivers and the destruction of the flora and fauna of the river ecosystem. When it is not dumped into rivers, it ends up killing the fertility of the soil. Further, there has been an exponential rise in the occurrence of landslides on account of cutting the rocks at high angles, which is akin to inviting disaster. While we don’t pretend to be experts on the matter and would refrain from issuing prescriptions to the government, we certainly want to be wary of the consequences of this development business, which has earned the ire of the veteran geologist, K.S. Valdia, who has called the Char Dham project meaningless. Another senior environmental scientist and scholar, Maharaj Pandit, draws attention to how the rampant construction of dams and roads in the Garhwal region has led to a change in land use pattern and is all set to amplify the effects of heavy rain in the future. In other words, a replay of the 2013 tragedy is not unlikely. Even if we were to ignore all of the above, eminent seismologists have warned of the high probability of a devastating earthquake upward of 8.5 in magnitude in the Garhwal-Kumaon region. This is really bad news and what is worse is that the Indian government has commissioned these grand road projects in a high-risk zone without carrying out a proper seismic hazard study.

A question of numbers

It finally boils down to the same question that our video had raised – should the government be promoting mindless mass tourism in an eco-sensitive place like Kedarnath? And where should they draw the line? We admit that there are no easy answers and that is precisely why such questions must be asked persistently.

It is important to mention the geostrategic importance of building roads in the Himalayas in view of the constant threat from China on the other side of the mighty peaks. Further, there is the question of local economy, which has thrived after Uttarakhand was carved out of Uttar Pradesh followed by a boom in tourism. More pilgrims are good for the local economy and while those employed in the “eco-tourism” industry are wont to throw around terms such as sustainable development and reduction of carbon footprint, they are generally not bothered about what these terms actually mean. Eco-tourism is used more often as a virtue-signaling invitation to attract more tourists than with a genuine intent of adhering to its professed principles. These are no doubt terribly important realities to take stock of but they cannot be allowed to cloud our sense of judgement resulting in vested interest groups dictating our civilizational agenda.

We discovered a proclivity among some vocal natives to disparage voices that they find inconvenient by painting them as alien and uninformed. One such person, speaking on behalf of all locals, made a statement that Garhwali villagers are not too worried about the state of ecology because making ends meet is more important to them. Also, as per him, they find it absurd that they are expected to make sacrifices when urban folks don’t sacrifice anything, sitting as they are in airconditioned rooms. While there is some truth in the claim that a narrative has taken hold that more tourism is always desirable, we are not entirely sure if the concern for ecology has been thrown in the dustbin.

The locals have been at the forefront of afforestation drives, they have a history of agitating against the construction of dams, including the still very risky Tehri dam and some today are genuinely repelled by the new proposal of “dark tourism” that the government seems to be pushing. Uttarakhand, by virtue of being born in the 21st century and owing to its unique geography, was founded on the vision of sustainable development in which ecological sensitivity and local autonomy were deeply ingrained. Even today, the push for organic produce and floriculture has much currency among the natives as they know the unavoidable limitations that step-farming imposes on their commercial ambitions. We are thus constrained to conclude that those who invoke motivated distinctions between local and outsiders do so because they have nothing else to say.

We wonder why the suggestion for the regulation of pilgrim traffic to Kedarnath is being interpreted as some sort of a communist conspiracy. Lesser pilgrim traffic does not necessarily translate to a reduction in tourist influx in general because there are other forms of tourism that can be promoted for spreading the human footfall over a larger area. Although any kind of visitor adds to the strain on the delicate ecology of the region, the least that policymakers can do is to ensure that it is not skewed in one direction. Accordingly, the numbers can be evenly distributed between religious, adventure, wildlife, and rural tourism.

It would not be out of place to mention here that though the care for Himalayan ecology is more than a worldly concern for us and that should have ideally made us the global trendsetter in tourist management, other countries with no ‘spiritual baggage’ seem to have done better. The benefits of reduced footfalls have impelled governments all over the world, from Peru to Croatia to Indonesia, to introduce measures to cap the footfall to places that are in danger of being overrun by the crowd. Maybe we can learn a thing or two from these, as they say in corporate lingo, best practices.

Conclusion

The reader may have found this article to be only an elaboration of the disconcerting points raised in Upword’s video rather than something more comforting. But the intent behind this article and the video has been to frame the problem in a clear civilizational context as opposed to endorsing this political party or that. Politically vocal Hindus reflexively associate the ecological discourse with leftist politics and do not engage with these problems independently, having grown accustomed to placing their trust in the secular state and doing nothing, save outraging on the social media. As a result, they have developed blind spots towards the civilizational imperative of conserving the natural heritage of India, which as we have shown above, is synonymous with our religious heritage. This leaves the field open for vested interests of all kinds to obfuscate the already difficult-to-grasp truth about the dangers to our sacred ecology. By framing the problem in the false binaries of Local vs Outsider or BJP vs Congress, we not only preclude the possibility of a constructive rational debate, but we also fail our Gods. The Puranas tell us that Kedarnath is Shiva with his back turned towards the Pandavas but by outsourcing our personal responsibility of protecting the shrine to the secular State, we turn our back towards Shiva.

Leave a Reply