Introduction

During one’s nascent years in India, the good and the bad in the Pakistan story were the Nehru-Gandhi duo and Jinnah respectively. Our history books gave us a clear view of the subject. It is another matter that historians of Pakistan simply reversed the heroes and villains. In such linear narratives, even the historians on either side fell into the trap of assessing the Partition story based on these central political characters. In this medley, a westerner writing a book like Freedom at Midnight made Lord Mountbatten the hero and caricatured all the rest.

However, the premise of many historians remained that the idea of Pakistan was vague and Jinnah mainly used this as a bargaining political chip to demand from the Congress and the British an equal status for Muslims in an undivided India. The formation of Pakistan was almost an unintended consequence in the process of independence from colonial rule. Venkat Dhulipala shows brilliantly in this book Creating a new medina, an effort of a decade of intense research, that this was far from the truth. He traces the multiple intertwined factors which crystallised and later achieved the state of Pakistan.

Creating a New Medina gives a breath-taking view of the story of Pakistan. Beginning with the Lahore Resolution in 1940, where the idea of Pakistan first formalised, to the partition and independence in 1947, he traces the turbulent years, especially in the United Provinces (roughly the present-day Uttar Pradesh) which was at the forefront of activism regarding Pakistan. This well-researched history book, of interest to both the professional historian and a layperson, almost reads like a thriller.

Apart from many valuable insights, the book prominently debunks the idea that Pakistan and the concept of an Islamic state was anything but vague. This is a must-read book for all Indians fed again on a simplified history of India’s independence predominantly written by the victors in the post-independence period. The political heroes and villains, especially, were not white and black characters but were as grey as possible typical of all politicians across time and space.

Venkat Dhulipala was born in coastal Andhra Pradesh and his formative years were in Uttar Pradesh. He graduated from the University of Hyderabad and then went to the US for further studies and later a doctorate. He is now an Associate Professor of History at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington specialising in colonial histories. Based on his Partition studies, an interest which he acquired serendipitously, he went on to write this book. The book generated debate and heat from various scholars and historians but the author could prove his point by detailed rebuttals.

Mohammed Ali Jinnah

Mohammed Ali Jinnah was the most important character in the Partition story. He was also the most unlikely candidate to be arguing for an Islamic state. Apparently, Gandhi knew the Quran more than Jinnah. The latter was a westernised lawyer hailing from Gujarat- the same place as Gandhi, in fact. His grandfather converted from Hinduism to Islam and one of the great speculations in the Indian sub-continent has been what would have been the turn of events had Jinnah’s grandfather not converted.

Jinnah was not religious by any standards. In fact, his personal traits of smoking, taking alcohol, comfort only in the English language, and rarely making any religious pilgrimages would not qualify him to represent an ideal representative of an Islamic state. He was bargaining for an Islamic state even though a group of biographers paint him as a secular person battling almost for Hindu-Muslim unity. A few saw him as another Prophet trying to establish a new Medina. A Muslim supporter declared that like the Prophet who migrated with a few of his followers to Medina, Jinnah went from Gujarat to a majority Muslim area to set up an Islamic state.

Even his hard-core critics agreed on his personal honesty and integrity. However, as Venkat Dhulipala shows with much evidence that the idea of Jinnah battling for a secular state where the Muslims could live in peace is erroneous. Jinnah conceptualised Pakistan as an Islamic state which would play a central role in the Muslim world and take the role of by then collapsed Turkey. He spoke in support of Pakistan as a strong force taking up Muslim causes across the world including Palestine. He was also clear in the idea of Pakistan to counter all imperialist forces, including the Hindu type.

Only he was unsure of the nature of the Islamic state and how much would the ulama control the constitution. During his time, the friction between the Sunnis and Shias had come to the fore. Jinnah himself was a Shia. Interestingly, when he died, there was a Shia private ceremony and a Sunni public ceremony held by the chief maulvi.

He also knew that United Provinces (present Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand) would not be a part of Pakistan despite much physical and intellectual support coming from there. At a public function, Jinnah claimed that he was willing to sacrifice the interests of the two crore Muslims in the rest of India for the sake of the seven crore Muslims in the majority Provinces for the Muslim brotherhood.

Muslim League Party

The Muslim League was at the forefront of the Pakistan idea and it was a more than formidable challenge to the Congress who were batting for a united India. In the decade prior to independence, the Muslim League grew in strength and transformed from a party of elite Muslims to one with mass mobilisation and popular support. It had considerable support from an influential section of the Ulama. The Congress initiated a ‘mass contact’ programme to induct Muslims into its fold but could not withstand the Muslim League challenge. The League grew from strength to strength in the run-up to Partition.

In the crucial elections before independence, which was almost a referendum for Pakistan, the Muslim League won with a thumping majority. The League was vociferous in support of Muslim causes and was critical of the Congress. It was clear to them that a united India would spell only doom for Muslims.

It launched many attacks against the symbols of India’s national life as visualised by the Congress: Gandhi’s Wardha scheme of education became a ‘Gandhian totalitarianism’ to brainwash students into non-violence; it objected to the history which gave importance to Muslim rulers like Dara Shikoh and Akbar who batted for syncretism; it objected to the history which glorified Hindu rulers like Shivaji; it fought against the replacement of Urdu with Hindi; it was critical of the flying of the tricolour in government institutions; and it had objections to the singing of the Bande Mataram song during official functions and government schools. Their grievances were many against the symbols of Indian culture which they saw as plainly Hindu.

Though the Muslims in Congress tried to downplay or give explanations to the various cultural symbols, the Muslim League was generally unmoved. The Muslim League, the most important political force in the creation of Pakistan, had a clear stance against the Hindu dominated Congress. Later historians tried to paint Jinnah with a secular brush in only trying to protect Muslims in a united India and not really ‘anti-Hindu’. However, the author shows clearly that though there were some modifications in their agendas such as fighting the ‘British imperialist’ forces, the purpose of Jinnah and the Muslim league was clearly for the creation of Pakistan as a new Medina for the Muslim world, a role which Turkey fulfilled for long till it collapsed by the end of first world war.

Ulama

The ulama argued strongly for Pakistan in Muslim-majority areas of the sub-continent as a sovereign state where Muslims would be free from both Hindu and British domination. There would be breaking down of barriers of race, tribe, class, sect, language, and region among Muslims. But there was indeed a lack of clarity on the nature of the Islamic State and the role of Shias and other sects of Muslims in the new state.

A section of Deobandi ulama formed a political party Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind (JUH) and opposed strongly the Muslim League as well as the partition of India. They and their allies in the Congress party dismissed the possibility of an Islamic state materialising in Pakistan, ridiculed Jinnah’s ability to lead Indian Muslims into that glorious Islamic utopia, besides questioning Pakistan’s ability to survive as a sovereign independent state giving economic, military, political, and social reasons. They instead upheld the ideal of composite nationalism of all Indians, stoutly opposed the Partition, and contested Muslim League’s ideas through public meetings, political conferences, and the columns of the Urdu press.

However, the more powerful section strongly advocated the two-nation theory. It gave major support to the Muslim League and Jinnah as the ‘sole authoritative representative organisation of the Indian Muslims’. Fatwas were regularly issued warning Muslims from joining the Congress. The utopian idea of Pakistan as an Islamic state and a New Medina was clear in their speeches and writings. As a metaphor, they wanted Jinnah to lead the ship to the coast, that is, till the independent state came into being. The final journey to the port or the destiny of Pakistan after Partition would be through Sharia, however.

The author shows in the book that the ulama was involved in the politics of Pakistan right from the beginning and there were never any doubts about the religious nature of the new state. A few clerics like Seoharvi interestingly argue against the two-nation theory but again the secular arguments combine with religious arguments. He thought that dividing the nation would make India pass anti-proselytization laws and this would reduce Islam from an ethical, cultural, and ideological programme to a mere geographical programme. Pakistan would thus be detrimental to Muslim interests from the viewpoint of tabligh or proselytization. The ulama thus had a very important role in mobilizing public awareness. Ironically, even the critics of Pakistan from ulama found religious reasons (protection of Islam) to counter Jinnah and the Muslim League.

Aligarh Muslim University

The Aligarh Muslim University faculty and students played a crucial role in gathering support for the Muslim League even sacrificing their regular studies. The author describes how two factions emerged from the University- the MUMSF (Muslim University Muslim Student’s Federation) aligned to one ABA Haleem, a senior faculty member; and the MUML (Muslim University Muslim League) aligned to the Vice-Chancellor Dr Ziauddin. The latter group seized the initiative and helped the Muslim League win elections. One member declared,

Aligarh being the arsenal of Muslim India, must also apply the ammunition in the battle for the freedom of the Great Muslim Nation.’

The MUML described the physical and mental criteria for the students to take part in the movement even as instructions went to the teaching staff to design appropriate courses and lectures for the students. These would cover Islamic history; the history of the Muslim League and its comparison with the Congress; the need for Pakistan; practical programs of speaking, group discussions; and visiting different towns and villages to spread the message of Pakistan. The leaders of ML and Jinnah too appreciated the utility of the students and faculty in their fight for Pakistan.

The author informs that in the crucial elections of 1946, regarded as a referendum on Pakistan, almost five hundred students from the Aligarh Muslim University campaigned for the candidates not only in Punjab but in the North-West Frontier Province, Sind, Assam, and Bengal. Jinnah was enthusiastic to get the support of the students though he was uncomfortable with the university factions and politics. The services of the students proved critical to the ML campaign in all the provinces of British India, especially the United Provinces (UP). It tilted the balance in many constituencies in favour of the Muslim League.

The AMU students and faculty were indeed useful allies in the creation of Pakistan despite knowing fully well that UP would never be a part of Pakistan. As a letter to the editor in the newspaper, Dawn said,

The Muslims in UP have proved that though their province is not yet Pakistan yet they are solidly behind the Muslim League which rightly claim to represent the Muslims of India.’

The Communists

This book shows the importance of the Communists in the creation of Pakistan, arguably second only to the Muslim League. EMS Namboodaripad stated that ‘the CPI would wholeheartedly support ML candidates in the forthcoming elections and put up communist candidates in general constituencies against the Congress.’ Communist intellectuals blueprinted the case for Pakistan with academic arguments. Communist Party of India thought, like pre-revolutionary Russia, India was a land of submerged nationalities rather than a composite national unit. Each of these had a right to set up a sovereign state of its own. Thus, the Muslim people in Bengal (East) and Punjab (West) could set up a separate federation of Pakistan. However, the ML itself was quite suspicious of its motives.

Arun Shourie and Sita Ram Goel elegantly trace the duplicity of the Communists during the years before independence when world events affecting Russia modified their stance radically. Briefly, soon after the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia in 1917, Communists started speaking of India as a battleground between ‘forces of capitalist reaction and forces of proletarian revolution.’ Gandhi, by his hold on the masses and rooted in traditions, was their enemy.

There was a flip-flop in 1935. The anti-Bolshevik tone of Nazi Germany scared the Soviet Union. The Communist International appealed to the Communist parties in various countries to build pressure on their governments for a ‘broad national front of all anti-fascist forces.’ Now, the Communist Party of India joined the Indian National Congress and pushed for a mass movement against the conservative British government.

Then in 1941, Hitler invaded the Soviet Union. Simultaneously, the Congress launched the Quit India Movement in August 1942. The Communists in the Congress opposed the Quit India resolution; now the ‘imperialist war’ became a ‘people’s war’ simply because an enemy of Britain (Germany) invaded a friend (Soviet Union). Britain became a friend. British ‘imperialism’ became British ‘bureaucracy’; the Muslim League, a ‘spokesperson’ of the Muslim mass upsurge; and the demand for Pakistan, a legitimate expression of Muslim nationalism. Communists adopted this party line and collaborated actively with the British by sabotaging the Quit India struggle in 1942.

Baba Saheb Ambedkar

Dr Ambedkar played a significant, but not much known, role in the Pakistan idea by writing a 400-page book Thoughts on Pakistan (also named Pakistan or the Partition of India) within four months of the Lahore Resolution. It was an incredible achievement as he laid bare all the pros and cons of the idea in the book along with many appendices, facts, figures, and maps. The author says that this was a ‘prescient, prodigious work of scholarship by a brilliant mind, which would go on to serve as an indispensable reference to all the parties in the conflict…’

He wrote this book as an impartial and neutral observer. Ambedkar agreed on the popular Muslim sentiment to create a separate nation and unambiguously supported the Muslim League’s Pakistan demand. However, he also made a series of arguments to Hindus to concede the demand for their own benefit. The Hindus and other minorities would be able to live in peace in a new country devoid of the Muslim League’s ever-increasing demands. An undivided India would be a worse alternative, in fact, than Pakistan itself. Ambedkar was scathing in his attack of Hindus for their refusal to accept the reality of Pakistan on some emotional and non-rational arguments.

Ambedkar had some rather harsh things to say about Indian Muslims too during his time which scholars have glossed over completely. As astute Muslim politicians are reaching out to Dalits to forge a synthetic unity and create divisive narratives against Hindus, it would be well to revisit Dr Ambedkar’s book. He was harsh to both Hindus and Muslims but essentially asked the Hindus to get rid of the Muslim League menace by accepting Pakistan and live in peace.

He nurtured the concern of Muslims accepting Hindu dominated rule. Ambedkar simply thought that an independent India with a large Muslim population would be an impractical idea. The extra-territorial loyalties of the Indian Muslims, seeing themselves as members of a universal Islamic brotherhood, were a concern for Ambedkar. The Indian army as it existed then, he pointed out, was predominantly Muslim in its composition which would not only be of doubtful loyalty but will be hard to control and discipline for a united India.

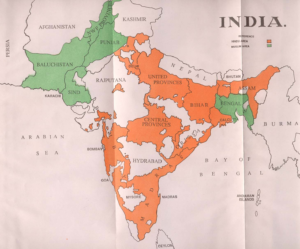

The Majority Provinces and The Minority Provinces

Sind, Punjab, Balochistan, North-West Frontier Province in the west; Assam and Bengal in the east were the Muslim majority areas. Broadly, it was clear that these majority provinces would go in the formation of Pakistan. There were about 7 crore Muslims in the majority areas and two in the minority areas which included the United Provinces too (roughly UP and Uttarakhand of today). There were about three crore non-Muslims in the majority areas and there was always a debate regarding their status of staying in an Islamic state.

There were intense debates on all sides and at all levels to address these tricky issues. Perhaps, here was the biggest internal clash of the ideal of an Islamic state based on Sharia and the secular ideal of modern states. There was much ambiguity on the status of the remaining Muslims and Hindus in India and Pakistan respectively. Mass migrations were one option but it was quite evidently an impractical idea on a broader scale. Interestingly, for the protection of Muslims in the United Provinces, apart from the creation of corridors running across India connecting East Pakistan to the West or creating distinct Muslim cities, the ‘hostage population theory’ came much into vogue. Any trampling of Muslim rights in India would have serious repercussions for the Hindus in Pakistan.

Ironically, there were some voices that proclaimed that the interest for Pakistan was much less amongst the population of the majority provinces. The Muslim League, which perhaps was the sole representative of the Muslims had a larger say and presence in the minority areas than in the majority provinces.

The Independent Opinions

The Press and the media were a vibrant arena where readers from across the country made their opinions about Pakistan clear. There were some strong ideas for and against the idea of Pakistan. The author shows in detail the intense debates which happened in the public arena of the citizens. Citizens also wrote directly to the Qaid discussing the idea of Pakistan. Interestingly, many times the arguments against Pakistan by the Muslim citizens and even the Ulama supporting a composite nation cited the need of staying united to spread Islam. Undivided India would be a better target for proselytization than a divided India which would more likely bring in laws preventing the same.

In fact, the Ulama segment of Madani against the Muslim League thought that the latter was not doing enough for Muslims in India and even in far off places like Palestine and Zanzibar. The detailed arguments both for and against which newspapers carried as a series of articles make for some fascinating reading.

The Poets and The Writers

The writers were an important intellectual muscle articulating the feasibility and necessity of a separate nation. The UPML (the United Provinces Muslim League), despite many internal and intense political frictions, appointed a Committee of Writers headed by a Lecturer of English at the University to produce a series of pamphlets that could become a part of the popular literature on Pakistan. This committee also included other people from academia and newspaper editors too. The pamphlets they produced were an indicator of the growing common sense about Pakistan at Aligarh and Muslim north India at large, says the author. They also served the purpose of informing the international audience.

The ideas were clear on the unfair deal which Muslims were bound to receive in an undivided India. Various authors gave detailed economic, religious, educational, political, and sociological reasons for Pakistan. For example, one professor of History from Delhi University, Ishtiaq Husain Quereshi, contributing to two provocative pamphlets stressed that an Islamic form of government was far superior to liberal democracy, capitalism, or totalitarianism. Liberal democracy was but a ‘Jewish conspiracy’ and in fact ‘Hitler was not wrong when he identified the democracies with international Jewry.’

In the meantime, many poets contributed poems, songs, and ditties recited by the students while garnering public and rural support. The author manages to glean some of these from a surviving rare volume released on Jinnah’s birthday on 25 December 1945 from Bombay. The fiery poems, compiled by Ramzi Illahabadi, give us a wonderful indication of the youthful enthusiasm amongst the Muslim students across India for Pakistan. Under the garb of Communism, there were poets like Asarul Haq and our very own Majrooh Sultanpuri, who later set blazing standards in Bollywood with his romantic poetry, eulogizing the notion of Pakistan.

The Turnaround After Independence of United Provinces Muslims

The hard reality of the Partition finally hit the Muslims in the United Provinces. Communal tensions came to the fore, the powerful politicians of ML migrated to Pakistan, and the UPML found itself in complete disarray. Though Jinnah bravely invoked various solutions like Pakistan coming to the help of Muslim brethren; threatening retributive violence against Hindus in Pakistan; or migrations to a new state, they were all clearly impractical after Pakistan came into being.

The ML in the United Provinces folded up and the Congress could appropriate the Muslim vote. The leaders now asked its people to vote for the Congress if they wanted democracy and not Hindu Raj against their interests. There was the testing of Muslim loyalty as many Muslims started expressing regret in supporting Pakistan and some even publicly speaking from the nationalist viewpoint on the troubling issues of saluting the national song and choosing Hindi over Urdu. The painful transition was also evident in the Aligarh Muslim University which suddenly turned secular in their outlook with Muhammed Habib, Professor of History, proclaiming that U.P. Muslims were ‘repentant of the League vote of 1945.’ The Progressive writers and poets, who thundered for Pakistan, but remained in India for whatever reasons now started working in the new language of secularism, socialism, communism, and even atheism.

A few voices in the community asked the Muslims to withdraw from politics and return to Islamic learning and self-improvement. The most significant statement was when Muhammed Habib says, ‘as heir to the great Muslim culture of the Middle Ages, we simply refuse to be moved into that cultureless land where an alleged devotion to Islam begins and ends with the hatred of Hinduism.’ It is thus easy to imagine the plight of Muslims remaining in India after the Partition as their loyalty came into severe questioning.

Pakistan After Independence

Finally, the Partition happened, an event that led to the death of one million people and the forced displacement of another twelve million. In fact, it is the largest recorded movement of population in human history. The chaos and the bloodbath are all too well documented in our books and movies. The trajectory of Pakistan in the post-independence period became discordant with the projected ideals in the pre-independent era.

Over the decades, the basic lack of clarity in the application of Islamic principles in building up a secular constitution explains the ongoing struggles between Islamic groups and the political establishment over the definition of Pakistan’s identity. One political scientist Christophe Jaffrelot says that Pakistan’s postcolonial travails is because it lacks a “positive” national identity and possesses only a “negative” identity in opposition to India.

Venkat Dhulipala says elsewhere that the modernists’ vision of an “Islamic” Pakistan did attain hegemony after 1947, but it has remained shaky. Islamist visions and the ulama has fiercely contested, constrained, and limited the modern secular view of an Islamist state. Pakistan is now a heady and complicated mix of constitutional democracy, religious clerics keen to guide policies, and an ambitious army.

The non-Muslims who remained became second-class citizens even in Jinnah’s day. They could not join the ML, which only admitted Muslims. The minorities quickly realized that it was not a happy place to be; as an example, Dr Ambedkar was clearly unhappy when Pakistan did not allow the migration of the Depressed Classes from Pakistan to India. They did not want to lose the workforce involved in menial unwanted jobs.

The plight of mohajirs (mainly the United Provinces migrants) is all too well documented. The exiled leader of the MQM (Muttahida Qaumi Movement; previously Muhajir Qaumi Movement) made a dramatic statement in 2004, much to the dislike of Pakistan powers, that the Partition was ‘the greatest, greatest blunder in the history of the mankind.’ Similarly, other sects like the Shias and the Ahmadiyas too face discrimination and are a target of terrorism.

The Soviet Union wanted a base after British departure but the plan failed even as Pakistan became a base for American interventionism instead. The Communists also failed in their own conception of a Pakistan for which they fought quite aggressively. The ML, though enlisting their support, was however clear that Pakistan would never be a Communist ideal but an Islamic state. In another characteristic flip-flop, the Communists in India have been blaming the Partition on those very forces of positive nationalism which had fought the Muslim League.

Conclusion and the Indian Story

Pakistan was a conception of an Islamic ideal placed in the centre of and controlling the global ummah. As Venkat Dhulipala says,

Jinnah portrayed Pakistan as a vector for pan-Islamic unity on the world stage, which would be a bulwark against the depredations of both Hindu and Western imperialisms.’

No amount of invoking the personal ‘irreligious’ traits or the ‘secular’ nature of Jinnah can counter this fundamental truth.

Meanwhile, India took the route of unimaginative secularism imported from the west instead of declaring itself as a Hindu state. Ironically, the Congress all throughout painted as the enemy of the Muslims, became the greatest friend of the Muslims. After independence, the Congress became so involved in this role that perhaps due to the abnormal appeasement policies, the Hindu majority at one point simply detached itself from it.

The Congress became a spokesperson for a brand of secularism that took over the Muslim vote as a block. The Hindus, believing that the Congress would naturally act in their interests, continued to vote for it. In this secularism, the country lost a great opportunity to set the Hindu-tradition driven solutions for dealing with multi-culturalism and pluralism.

The Indian Communists and Marxists, despite being an insignificant political power, unfortunately, gained powerful positions in the academia which addressed all the fears of the Muslim League before independence. They whitewashed the brutal Islamic histories, reduced Hindu history to footnotes, removed any shred of pride in Indian culture and heritage, and set noxious narratives of the Indian past in the light of Marxist interpretations. Instead of looking at ourselves afresh, the themes of the exploiter and the exploited gave no different conclusions than the missionary-colonials: a degenerate Hindu religion giving rise to a malignant caste system.

In two generations, there was a complete deracination and de-rooting of the Indians by this unbelievable academic narrative. We lost an opportunity and now it is an uphill task to fight against such designs. Though democracy remained vibrant, despite some brief problems, India could not come together and offer solutions to the world. The imported solutions became our problems even as we failed to see that it is India that offers solutions to the world.

Venkat Dhulipala has written about a historical event of crucial importance in the fashion of a taut thriller and an incredible page-turner. The biased and agenda-filled historical narratives of the Partition depending on who wrote it has provided only skewed answers. The book is crucial in understanding that the Partition was not an outcome of the whims and fancies of a few individuals but an intertwining of a huge number of factors that came together in a complex manner which serious historians are still trying to decipher and make sense of.

Though extremely well received, there were the usual criticisms; a few were harsh. As the author writes in his detailed rebuttal elsewhere, a ‘secular’ image of Jinnah was critical in the narratives of liberal Pakistani historians. However, Jinnah and the Muslim League combining with the ulama; using religious metaphors to support Pakistan; deploying the rhetoric of war and hostage population theory; demanding transfers of the population; and widely combining ideas of Islamic nationhood and modern state become problematic for that image.

The main thesis of a sophisticated and intensive public debate on the meaning of Pakistan and Dr Ambedkar using unflattering words for Muslims caused apprehension in India. The worry was that Hindutva votaries could use this to paint the Muslims further in a negative manner. Nehru does not come off so badly in the book which might become discomforting to some who want to put everything bad in India today on Nehru! In fact, in one of the interviews, Nehru says clearly that Jinnah was not fighting for independence; he was simply fighting for Pakistan. These are unnecessary apprehensions as the book is not an argument about the innate enmity between Hindus and Muslims or a normative argument for Muslim separatism, says the author.

In an era where leaders have become icons for unquestioning worship, the book essentially shows the complexity of the many political leaders in dealing with the hugely difficult issues of another time. When one writes a book with almost a decade of research backing it, it would be not a good idea to attack the book on half-baked reading and poor understanding. Venkat Dhulipala sweeps off the criticisms easily and they stay insignificant. Every Indian with an inkling of interest in Indian Partition history should urgently read this book.

Leave a Reply