Scene One: Mid Nineteenth Century

Abolition of Slavery is a landmark event in American History. At the peak of American Civil war, President Abraham Lincoln abolished slavery as a strategic move to win the war through the Emancipation Proclamation (1863). Planters in the Southern states of America used to justify slavery on the ground of supposed racial inferiority of the Negros and need of Slavery as an institution for the benefit of the Negros. But what was the role of progressive American intellectuals of that era regarding abolition of slavery?

The voice against slavery was gaining ground in the preceding decades. This may give the reader an impression that progressive intellectuals sympathetic to abolition of slavery believed in equality of all races, as opposed to those conservatives who supported slavery as the right institution for upliftment of blacks. Such an understanding, however, would be deeply flawed.

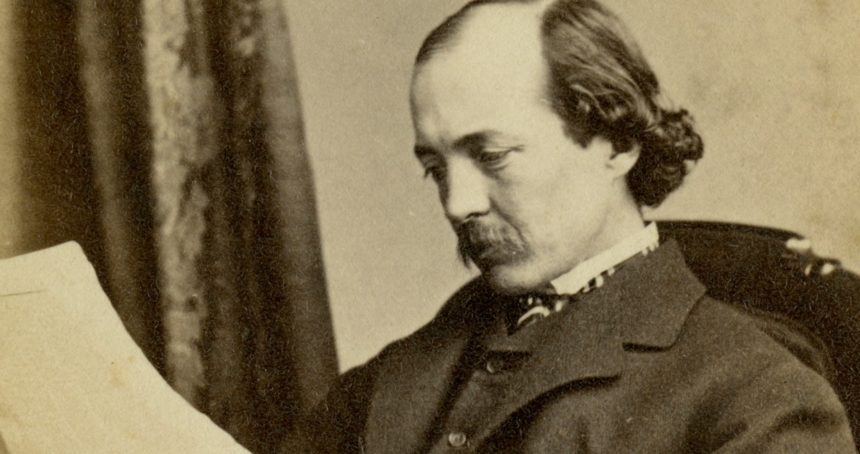

Frederick Law Olmsted was a versatile personality of that era. He was a farmer as well as a landscape architect, journalist, social critic and public administrator. He was commissioned by the New York Timeseditor in 1852 to prepare a series of articles about Slavery in the south. His famous book, The Cotton Republic (1861), was based on these articles which presented an all-encompassing picture of slavery. Eminent personalities of that era, including Karl Marx, were influenced by Olmsted’s views. What were Olmsted’s views exactly? He was firmly against slavery — not primarily because of exploitation of the slaves but mostly on account of the supposed inefficiency of the slaves who, in his understanding, accomplished one third to one half as much work as did “the commonest stupidest domestic drudges at the North.”

It is not Olmsted alone but other contemporary progressive intellectuals of the United States of the time such as Cassius Marcellus Clay and Hinton Rowan Helper had similar opinions, which formed the core of anti-Slavery argument of those times.

Do their arguments make sense? Absolutely Not. Eminent economic historians of the twentieth century—Robert William Fogel and Stanley L. Engerman—analysed American slavery in their book Time on the Cross (1974) for which Fogel was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in economic sciences. Their data-based work did dispel many popular false perceptions about slavery, in particular, the myth of Negro slovenliness. The Negros were definitely more hard working and more productive than free white labourers.

Fogel and Engerman further explain,

“The antislavery critics…conceived of blacks as members of an inferior race…Most expected that freed Negroes would have to be constrained in various ways if an “orderly” society was to be maintained.”

No wonder, “one of the biggest biological crisis of the nineteenth century” happened right after abolition of slavery when at least one quarter of the four million former slaves got sick or died between 1862 and 1870. (Jim Downs, Sick from freedom; 2012)

Scene two: Early Twenty-first century

A large number of American academics probably do not recognise Indian civilisation anything worthy of cognisance. The present West—American society being certainly at the forefront—is the product of the European renaissance in the Middle ages, which awakened the scientific exploration and risk-taking ventures of the West. At the heart of this revolution, argues Peter L. Bernstein in his book Against the Gods (1998), lies the Hindu-Arabic number system developed by the Indian civilisation and passed over to the West by the Arabs.

Sheldon Pollock is a scholar and a leading expert on Sanskrit. Pollock, a chaired professor in a reputed US university, is the editor of the Murty Classical Library of India, a project launched to translate many volumes of Indian classics into English. This shows identification of Pollock with the cause of Indian civilisation. Rajiv Malhotra’s book, The Battle for Sanskrit (2016), summarises Pollock’s views on Sanskrit and Indian culture. Pollock considers Sanskrit a Brahminical project and source of oppression in India. Sanskritic hegemony, Pollock feels, deprived India of all creativity. The Ramayana, according to him, is a socially irresponsible book.

Sanskrit connotes to the language of the cultured people by etymology. But Sanskrit is not really an exception; in civilizational projects, languages often evolve from the high culture of society and their names are indicative of this feature. For example, Mandarin is the imperial lingua franca of China (the language of the bureaucrats); Hebrew and Turkish are two artificially revived languages of the twentieth century by the cultural elites of the respective nations. Nevertheless, two most prominent compositions of Sanskrit, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, are both composed by authors belonging to the subaltern classes (left liberal terminology wise)—Valmiki was a highway robber and Vyasa illegitimate Child of a boat-woman. These epics form the heart and the soul of Indian culture. What can be better proof of the fact that Sanskrit integrated the masses of India?

Pollock is—very crucially—factually wrong too. He considers circa 260 BC as the birth of writing in India, overlooking the extensive evidence of writing found in Harappan sites (second or third millennium BC). Moreover, days when Sanskrit was India’s lingua franca, India was one of the most advanced country of the world in terms of science, technology and economic prosperity. It is quite naive to insinuate that Sanskrit is responsible for Indian inferiority (the claim of Sheldon Pollock).

Progressive Typification

The world-views of two leading progressive scholars of two very different generations show a similar pattern. Indeed, two examples are, by no means, sufficient to make a complete evaluation of the American progressives. However, they may bust some myths about American Progressives and their world-view which is often projected as neutral to race and religion.

A. Olmsted was for abolition of slavery but strongly believed in inferiority of the Negroes. Pollock is associated with promotion of Indian civilisation but strongly believes in inferiority of Indian civilisation.

B. Olmsted was factually wrong and prejudiced to consider the slaves as slovenly; but he pretended to be objective. Pollock’s worldview has also factual inconsistencies as explained above. He is supposedly objective; so it does invoke the question: does he nurture deep prejudices in his psyche?

C. Olmsted wanted Negroes to be constrained in an orderly society; he could not imagine a complete equality of the races. Pollock wants to send Sanskrit to museum as a dead language. He is utterly against revival of Sanskrit. Parity of Indian civilisation to its western counterpart is an unacceptable idea for him.

D. Though slavery was no progressive institution, slaves did survive as second class inhabitants in American society with receipt of almost 90% of payment made to the free workers (Fogel and Engerman, 1974). There was no systemic genocide by slave-owners. However abolition of slavery caused Negroes to perish in unprecedentedly large numbers during 1860s. Likewise, American conservatives are no friends of Indian culture. Indian cultural studies—while being dominated by western academic discourse—can survive without any state patronage from them. But it is difficult to conclude the same with Pollock as gatekeeper for Indian culture. Such a “friend” of Indian culture would probably end up being catastrophic.

Leave a Reply