In the previous parts, we looked at the ancient and mediaeval Indian economies and the impact of European colonialism on India and the world. The British left in 1947, our economy was in shambles, and there were many problems with the intellectual narratives set by the colonials. This part is an assessment of British rule in India and where we stood at independence.

Understanding Indian Economy: Ancient To Modern – Part 3

The British finally established themselves on Indian soil and had almost an uninterrupted run of nearly two centuries. When they finally left in 1947, our economy was in shambles, and there were many problems with the intellectual narratives set by the colonials. This part is an assessment of British rule in India and where we stood at independence. Some scholars are vociferous in equal measure for the positives the British gave us, but fortunately, they are a minority.

THE BRITISH PLUNDER OF INDIA (AND THE NAYSAYERS)

Britain impacted the Indian economy mostly negatively.

- Agriculture and industry did not develop in India.

- The industry in England developed from the raw materials exported cheaply from India.

- India was a market for the finished products.

This summarizes the British exploitation of India. Others were direct monetary transfers and use of Indian soldiers for the British army. The British rule is divided into two epochs, roughly a century each: the East India Company rule (1757–1858), and the British Government rule (1858–1947).

East India Company (1757–1858)

The East India Company (EIC) came as spice traders, first landing at Surat on August 24, 1608, forever changing India’s face. Later, they traded in silk, cotton, indigo dye, tea, and opium. After Jahangir’s permission, starting with Surat in 1613, they established factories across the Moghul empire. The Battle of Plassey (1757) and the Battle of Buxar (1764) were decisive for the gradual political involvement of the EIC. Progressively, they seized control of the Moghul province of Bengal (1757), Madras and Bombay provinces, and Punjab (from the Sikhs in 1848). They also drove out the French and the Dutch.

The EIC, a story of power and greed, made individuals rich despite the company faring poorly. The rice trade gave them a 900 percent profit. Robert Clive claimed £30,000 a year, about one-seventeenth of the then-annual revenue of Great Britain. Within the next half century after Clive, an estimated £500 to £1,000 million went from India to Britain. Till the mid-18th century, Britain mainly exported textiles and raw silk from India and tea from China. Bullion (gold) made the Indian payments; opium and raw cotton from Bengal made the Chinese payments.

Warren Hastings became the first Governor General in 1772. From 1785 on, there were no Indians in the high-level posts. In 1829, established districts throughout British India had individual British officials as final authorities. Never more than 0.05 percent of the population, there were only 31,000 Britishers in India in 1805, which in 1931 went up to 1,68,000 (about 60,000 in the army and police, 4,000 in civil government, 60,000 in the private sector, and the rest, non-professionals). After the first Indian War of Independence in 1857, the Mughal rule completely collapsed, and there was a power transfer from the Company to the Crown. This began the British Raj, with no further extension of direct rule over provinces governed by Indian princes.

The British Impact on Indian Agriculture

The Moghul tax system provided land revenue equal to 15 percent of national income, but by the end of the colonial period, land tax was only 1 percent of national income. However, the gains from tax reduction went to upper castes, zamindars, and moneylenders in the village economy, as Angus Maddison says (The World Economy). The landless agricultural labourers grew under British rule.

The irrigated area increased to more than a quarter of the land under British rule, compared with 5 percent in Moghul India. Improvements in transport facilities (railways, steamships, and the Suez Canal) helped agriculture by permitting some specialisation on cash crops and in exporting Indian indigo, sugar, wheat, cotton, jute, and tea to England. Hardly significant, as the latter two primary export items were less than 3.5 percent of the gross value of crop output in 1946.

Between 1850 and 1947, there was an increasing commercialization of agriculture, with crop production for sale rather than for family consumption—a deliberate policy to acquire more raw materials for British industries. The peasants now purchased foodstuffs for their domestic needs. Prior to developments in railways and trade, the famines were local food shortages due to crop failure. After 1860, these famines were purchasing power famines with high food prices, unemployment, hoarding, and speculation despite adequate transport. Famines most affected present-day Bihar, West Bengal, Orissa, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka. The immediate cause of crop failure was inadequate or unreasonable rains.

Additionally, the British created a land system where the property owners had to pay a fixed land revenue to the British but could charge the tenants as much as they wanted. The combination of landowners interested in high rents and moneylenders extracting high interest rates retarded agrarian development and made the cultivating class extremely poor. Unemployed craftsmen and artisans also shifted to agriculture as additional pressure. From the mid-19th century to 1931, the population proportion of those dependent on agriculture increased from 55 percent to 72 percent.

Finally, EIC converted large tracts of fertile land on the Gangetic River plains (nearly 1000 square kilometres by 1850) of Eastern India to poppy farms for the highly valued opium. This went to China in exchange for buying Chinese goods. This consequently led to opium wars in Asia; the major of them was between 1856 and 1860. After China became a part of the opium trade, by 1900, the government had increased cultivation to over 500,000 acres in the Ganges basin.

The EIC and later colonial officials had an exclusive monopoly on production, processing, and exports. As Sarah Deming (The economic importance of Indian opium and trade with China on Britain’s economy) analyses, EIC made opium an efficient and profitable business to service the cost of imperialism while also reducing its trade deficit with China. Except for the Bombay Parsis where the company had less influence, Indians investing in the opium business failed due to the strong EIC monopoly.

The British Impact on Indian Industry

The Industrial Revolution (1760–1840) reversed the thriving previous Indian exports with an increased demand for raw materials for British industry and the need to capture foreign markets for finished products. The inexpensive machine-made goods held a severe competitive advantage over the more expensive Indian handicrafts, India’s largest industry. Later, massive duty-free imports of cheap textiles (cotton, wool, and silk) from England and the unwillingness to give tariff protection caused immense damage to cotton exports from Indian modern mills.

Cotton mills started in Bombay in 1851, preceding Japan and China by two to four decades. Exports were half of the output. By the end of the 1930s, Indians were importing cotton from China and Japan in reverse. With increasing Japanese imports, the British introduced stifling measures to raise tariffs on non-British cotton cloth to 50 percent. Despite all this, Indian mills succeeded in increasing their production, producing 75 percent of Indian cloth consumption at independence.

Only when England rose to industrial supremacy did they advocate free trade in the latter part of the nineteenth century, emphasising the free import of machine-made manufactured goods but not machinery as such. Jute manufacturing, coal mining, steel, insurance, store purchase from Indian sources, and banking boosted in the first decades of the 20th century due to a combined effort of entrepreneurs (often Marwaris and Parsis); the nationalist Swadeshi movement; and some protective tariff measures.

However, lucrative jobs in many domains were with English agencies, intricately linked with British financing and shipping enterprises, which managed industrial enterprises and most of India’s international trade. Thus, the Indian capitalists who did emerge were highly dependent on British commercial capital. The British were also not keen to provide technical and managerial education to Indians.

Military Expenditure and Taxation

In 1922, India’s total expenditure on defence at 63% was significantly higher than many others: the UK (54%), Australia (48%), Canada (24%), South Africa (5.2%), Spain (17.6%), Italy (17.3%), France (20%), the USA (38%), and Japan (49%). These financed wars of imperial interest in Asia and Africa.

After the world wars, the Indian nationalist movement made it politically necessary to finance military expenditure in India by borrowing rather than local taxation. India could liquidate $1.2 billion of pre-war debt and acquire sterling balances worth more than $5 billion. Thus, it became costly to maintain the empire.

The EIC taxed the Indians severely for its extravagances and armed forces. Their taxes on land produce and salt generated almost 1 million pounds per year. The British enhanced taxes on land, trade, occupations, and commodities. In South India, taxes increased from 16% of the gross agricultural produce to 50%, and the calculation was based on the produce of a good agricultural year.

The tax burden was constant despite crop failure. These oppressive systems led to the decay of agricultural, industrial, and trading systems. In 1929, the tax for the people of India was more than twice that of the people of England. The percentage of taxes in India, as related to the gross product, was more than double that of any other country. Most of the taxes extracted went out of the country.

The ‘Drain’

British policies aimed for the prosperity of England and not of India. The peculiar summary of the colonial impact on modernising was India’s integration into world capitalism without taking part in the industrial revolution (Dr. Bipin Chandra). Dadabhai Naoroji (Poverty of India, 1876), MG Ranade, and RC Dutt emphasised the ‘drain theory’ of colonial exploitation.

A unilateral net transfer of wealth and capital from the country was responsible for hampering India’s development. The calculation of this money became an important component of ‘economic nationalism’. Till 1757, European traders purchased Indian cotton and silk goods in exchange for English bullion (gold and silver). After the transfer of power, Indian goods purchased with Indian money, generated through plunder and surplus revenues, went for sale in British markets.

“The Home Charges” were the expenditure to India, remitted to England, for the privilege of their rule and its services. The defence expenditure, civil expenditure, remittance of returns of investments, salaries, and pensions of European employees at abnormally high levels were the most objectionable forms of drain. India forcibly made payments on account of railways and irrigation works. On the capital invested in Indian private railway companies, the investors had guaranteed 4.5 percent returns, from Indian revenues, of course. This guaranteed scheme was wasteful because there was more capital invested than justified economically. Home charges also included European engineers’ and university professors’ salaries, allowances, and pensions to British Indian officials and army officers.

The public debt calculated for India was these Home charges plus the cost of wars waged by England inside and outside India. In 1858, the debt stood at 70 million pounds and rapidly reached 274 million pounds in 1913. The crux of the drain, according to Naoroji, was ‘unrequited exports’—exports without equivalent returns. There was a continuous transfer of huge quantities of gold, silver, precious stones, and other goods.

It is difficult to estimate the drain, or ‘Indian Plunder’ because of a lack of data. Charles Forbes stated in the House of Commons in 1836 that the total annual drain from India could be a little short of five million sterling. According to William Digby, between 1757 and 1815, an average of 17.2 million pounds per annum (a total sum of 1000 million) went from India to the English banks. In the last decade of the 19th century, the average annual remittance to England was 20 million pounds. Further wealth extraction was in the form of priceless manuscripts, antiques, jewellery (the Kohinoor diamond too), and so on, now in the British Museums.

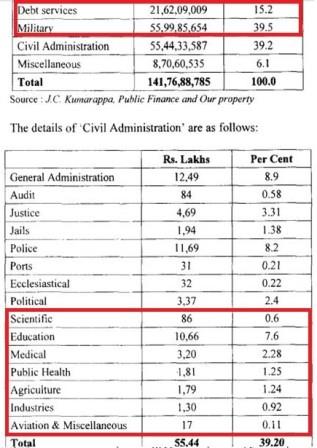

As an example of what the British government invested for India’s ‘development’, the tables show expenditure for science, education, public health, and agriculture as a percentage of net expenditure for the fiscal year 1925–26, including both the central and provincial governments:

Dadabhai quantified the economic drain at 15,000 million pounds for the period 1787–88 to 1828–29. According to R. C. Dutt, on average, ‘one-fourth of all revenues derived in India was annually remitted to England’. He further estimated that during the 1890s, 159 million pounds out of a total revenue of 647 million pounds went from India to England.

Another estimate showed that annual payments under the ‘Home Charges’ increased from 5 million pounds in 1856 to more than 17 million pounds by 1901–02. There was also a disproportionate tax burden. According to Dadabhai, the average tax burden in the poverty-stricken country was 14.3 percent of income in 1886, as against 6.92 percent of income in England. The EIC helped finance British industries in the initial stages of industrialization. The consequent shortage of capital contributed enormously to the destruction of Indian internal trade and industry. This reduced the country’s power to save and invest and, therefore, inhibited the country’s economic progress.

There are critics of the ‘drain’ theory. Some estimate the drain as a proportion of national income rather than public revenue. Thus, between 1870 and 1900, the drain varied between a meager amount of 0.4 percent and 0.7 percent of India’s national income. The critics question whether all payments constitute ‘drain’. Dividends paid to the EIC shareholders at the transfer of power could be a ‘drain’ on Indian resources. However, the same is not true for interest payments on loans for railways and irrigation works, as there were goods received or fixed assets created. The British capital for railways, irrigation, tea plantations, and jute mills was productive because it raised national income. Indians, by borrowing money from the cheapest capital market in Britain, should be grateful to British investors for filling the deficiency in India’s domestic capital resources. The payments were not a gift; they were for services rendered.

The nationalists contest this strongly and say that drain links with public revenue rather than national income. Secondly, even if relatively small, it continued for a period of not less than 50 years. They strive to show that whenever India’s colonial economic links in terms of foreign trade and the inflow of foreign capital were disrupted (the two World Wars and the Great Depression), the Indian economy, in fact, made strides in industrial development. Hence, the free flow of foreign trade and capital implied economic stagnation, while their absence (partial or total) allowed Indian capital to open avenues of industrial growth in areas choked off by imports.

Was the British India Economy an Unmitigated Disaster? “The Cambridge School”

Some economists, such as Tirthankar Roy, believe that the British impact was not a one-sided disaster because settling Europeans diffused their institutions, skill sets, and entrepreneurships across the world, including India. The drain is debatable, according to these thinkers. Tax revenue was only about 3% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 1931.

The Indian economy during the Raj was in fact a prototype of a classic liberal political economy—small governments and an unregulated open market. After independence, in an eagerness to break away from anything colonial, India implemented big state intervention and a closed economy—exactly the opposite of previous years. Deindustrialization also remains debatable since many skilled artisans survived imports from Britain, and they even contributed to the growth of the national income. Indian merchants set up factories on a large scale, which was problematic for many older models. In colonial India, national income grew, but at a slow pace throughout. Between 1900 and 1947, GDP increased by 60% and per capita income by 10%.

The armed forces expenditure was indeed huge, but this army also gave a fragmented land political unity like never before, albeit at the cost of agrarian development. Also, independent India inherited this army. Naval forces and port control fostered maritime trade in the Indian Ocean. The open economy, one of the biggest pluses of British rule, was compatible with Indian economic interests by creating a robust industrial capitalism with free movement of people, skills, and knowledge until the 1920s.

This centred in the urban port cities of Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras to make them industrial and educational centers. Many Indian entrepreneurs, especially Marwaris and Parsis, flourished, contributing immensely to the Indian economy. They built an industrial infrastructure by importing machines and personnel. There might have been some inefficiency, but the so-called Home charges were finally a payment for skills to join the world economy. The misinterpreted drain of the economic nationalist was for services contributing to national income, public goods, and political stability.

Foreign trade, exports of agricultural commodities, imports of machinery and skills, indigenous banking systems, and easy access to finance increased employment in Indian factories from near zero to two million between 1850 and 1940. Extraordinarily, GDP rose at a rate of 4%–5% per year between 1900 and 1947, comparable to other emerging economies. Outside Europe and the United States, 30% of the cotton spindles in the world were in India in 1910.

However, the slow growth of the agricultural economy and failure to make a dent in rural poverty made the Raj unpopular. Roy says that agriculture stagnated more due to factors like dry land, poor soil, precarious water supply, and overexploitation of land than ‘economic exploitation’. Also, there is no data to show high productivity previously showing a fall in the colonial era. Tirthankar Roy thus believes that there is no theoretical relationship between the desire for political freedom and the economic idea that free enterprise has damaged India. It served the nationalist struggle well but made debates on economic history difficult.

Post-independent India stopped free enterprise and slowed our growth. The big state transformed the agricultural economy and set the base for economic liberalisation, which should have come sooner. The dent in rural poverty caused by huge agricultural investments was something that never happened under colonial rule. Cosmopolitan capitalism with the addition of a large state would have been a better option, but it was unthinkable for the socialistic philosophy in power.

After independence, trade and foreign investment reduced to insignificance due to stiff government controls. GDP did grow higher than colonial levels, but this was from taxpayer’s money rather than commercial profits; this is not a sustainable strategy. The economic liberalisation of the 1990s, which returned India to openness, sustained the expensive agricultural system without leading to an economic breakdown. This was a return to colonial times, says Roy, but taking off on a sound agricultural base.

Criticism of The Return of Colonial Trends in Economic History

Some economists argue that colonial factors led to unprecedented economic development in India. The inhibiting factors in Indian development were overpopulation; shortage of capital; Indian social customs; values like lack of ambition; spending extravagantly on marriages; India’s geographical weaknesses; and climatic conditions. The indigenous control of the domestic market to about 70 percent at independence; 83 percent of deposits in Indian banks at independence; rapid import substitution of major consumer goods and certain capital goods, including iron and steel; growth of urban port cities; and so on, prove the beneficial result of colonialism.

Marxist scholars such as Professor Aditya Mukherjee (The Return of the Colonial in Indian Economic History) strongly condemn these colonial-friendly theories, almost suggesting that India was reversely exploiting England! For Marxist historians, in the colonial era, commodity circulation exclusively benefitted metropolises like London. There was the destruction of the traditional artisanal industry in India and the deindustrialization of the world’s largest exporter of textiles.

According to Mukherjee, all non-colonial developments in the 20th century occurred not because of colonialism but despite or in opposition to it. This period was not decolonization but a continuation of an altered and intensified form of colonial exploitation. Britain, having lost its industrial supremacy in the world by the beginning of the 20th century, emerged as the major financial center of the world. Britain maintained this until the Second World War by manipulating India’s currency, exchange rate, and financial policy.

Britain conceded substantially her industrial interest in the colonial market in favour of financial interest, thus using the colony as a source of capital. It was a switch from one imperial interest to another, not a switch from imperial to Indian national interest. From 1914, in the next ten to twenty years, there was an increase in ‘Home Charges’ (£ 20 million to £ 32 million); military expenditure (£ 5 million to £ 10 million); and interest charges on external public debt (£ 6 million to £ 14.3 million).

During World War II, defence expenditure increased from about Rs. 50 crores in 1939–40 to Rs. 458 crores (75% of the total expenditure of the Central Government) in 1944. This came about by increasing customs revenue, primarily import duties. The import duties on cotton goods had gone up from 3.5 percent in the 1890s to 25 percent for British cotton goods in 1931. During the Great Depression, the colonial government resorted to severe deflation, contracting currency repeatedly, and causing havoc in the Indian economy. A massive export of gold from India averted a total breakdown of the remittance mechanism. Between 1931–32 and 1938–39, more than half (about 55 percent) of the total visible balance of trade was through the net exports of treasure and gold.

Britain took massive, forced loans from India (the Sterling Balance) of about Rs. 17,000 million (estimated at seventeen times the annual revenue of the Government of India and one-fifth of Britain’s gross national product in 1947) at a time when over three million Indians died of famine! After the war, Britain made a serious bid to default on the repayment of the loans. State policy smothered the efforts of Indian entrepreneurs to enter frontier areas of industry during the Second World War. Stagnant agriculture was the weakest point of British rule in an agrarian country, contributing a mere 6 to 8 percent of the national income and employing 2.3 percent of the labour force.

Angus Maddison shows that India was the largest economy in the world for the entire thousand years of the first millennium, accounting for close to 30 percent of the world’s GDP. Till the beginning of the 18th century, India’s was still contributing about 25 percent of the world’s GDP, more than eight times that of the United Kingdom. India’s share was reduced to a mere 4.2 percent in 1950. India faced near-famine conditions repeatedly in different areas in colonial times. The Bengal famine of 1943, just four years before the British left, claimed more than three million lives. Between 1946 and 1953, there was an import of 4 million metric tonnes of food grains worth Rs. 10,000 million, seriously affecting India’s planned development after independence.

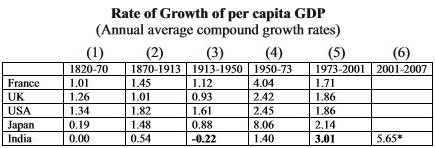

In stark contrast to other narratives, post-independent economic policies based on Nehruvian socialism were a success, according to Mukherjee. During the first three plans, Indian agriculture grew at an annual rate of over 3 percent, a growth rate more than eight times faster than achieved during the half century (1891–1946) of the last phase of colonialism in India. The per capita income grew at 1.4 percent in the first couple of decades (about three times faster than the best phase, 1870–1913, under colonialism) and much faster at 3.01 percent in the next 30 years. Industry, the value of fixed investment, and the rate of capital formation (33% of GDP in 2005–06, about five times the colonial rate) grew sharply in the post-independent period.

In 1965–66, as compared to 1950–51, the installed capacity of electricity was 4.5 times higher, the number of towns and villages electrified was 14 times higher, hospital beds were 2.5 times higher, enrolment in schools was 3 times higher, and admission capacity in technical education was higher by 6 and 8.5 times, respectively. This happened despite the persisting reasons for India’s stagnation, according to colonial-friendly theories, says Aditya Mukherjee sharply.

In the final part, we shall look at the Indian economic story after independence. There have been many contradictory claims and obfuscations. However, despite all the hurdles in understanding the true picture due to the huge volume of ever-increasing data, one can make a gentle claim that it has been an upward trend. The high population seems to be both an advantage and a disadvantage. For a layperson, this can get a little confusing.

.…continued in part 4.

Leave a Reply