In the first part of a 5-part series, Dr Pingali Gopal introduces the ideas of the great Indian philosophical systems to the uninitiated.

Western Philosophers equate philosophy with only western thought which, puts philosophy between theology and science, and in turn, is either ignorant or dismissive of Indian thought.

Indian philosophy (or Darshanas) does not have an extreme reverence for science and because of the biases of the West, and resulatantly has disappeared from popular discourses; being termed ‘religions’ and hence lacking any validity in a ‘secular’ world.

Dr Gopal delves further into classification of Indian systems as orthodox and non-orthodox on the acceptance or rejection respectively of the Vedas as a reliable authority, and uncovers depths of Jainism, Buddhism, Samkhya, Charavaka and Nyaya-Vaisheshika philosophies for the uninitiated.

Further installments of this series will foray into the other orthodox and non-orthodox branches of Indian philosophical systems.

Philosophical Systems Of India – A Primer – Part 1

INTRODUCTION

This 5-part series aims to introduce the ideas of the great Indian philosophical systems to the uninitiated. The author claims no expertise or primary scholarship in the subject matter but attempts to disseminate some of the readings he has had in a summary form to some of the curious but ignorant. The books of Ramakrishna Puligandla (Fundamentals of Indian Philosophy), Karl Potter (Presuppositions of Indian Philosophies) and Chittaranjan Naik (Natural Realism and the Contact Theory of Perception) form the core basis of these essays. Hopefully, this should stimulate the readers to explore further and understand how rich and brilliant the Indian systems are and how they significantly compare and contrast with western philosophies in dealing with basic existential questions.

A strictly materialistic or ‘scientific’ view of the process of perception has caused deep troubles for the western philosophical world to date. Indian thinkers and philosophers had a different and perhaps a better understanding of the process of perception which they covered in their treatises almost a thousand years back. It is the most unfortunate debacle of our education systems after independence, a continuation of the colonial legacy, that they ignored teaching the growing generations the richness, depth, antiquity, and sophistication of Indian philosophy.

Philosophy deals with the most engaging questions for humanity: the purpose of life and Universe; reality status of the world; the presence and role of God; the matter-mind relation; and so on. Philosophers equate philosophy with only western thought which, in turn, is either ignorant or dismissive of Indian thought. This is surprising, because any person, irrespective of time and place, can have philosophical insights applicable to the whole of humanity. Thinking about some basic questions concerning humans cannot be the sole prerogative of a narrow group of people (mainly the White Europeans of the West) looking only through certain lenses (either Christian theological or its social sciences which is many times a secularized theology) developed in their cultural milieu.

The West puts philosophy between theology and science. As Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) says (History of Western Philosophy), like theology, it speculates on matters of indefinite knowledge; like science, it appeals to human reason rather than to the authority of a tradition. The separation of theology and philosophy did not happen in Europe until the Reformation (16th century CE). When we accuse Indian philosophy of being ‘religion,’ it is an application of a post-Reformation prejudice (religion – a matter of faith; philosophy – for self-reflection or critique but nothing about God or the soul). Hegel (1770-1831), the German philosopher originated this prejudice and largely fashioned the Western image of India. As Adluri and Bagchee say (The Nay Science), the standard themes were: India only developed an abstract Absolute; it lacks a historical sense; it does not know of concrete individuality; and so on. Once Hegel sent Indian systems to departments of Religion and Indology, Philosophy never reclaimed it.

Indic philosophy has an overriding concern for its ‘soteriological’ power; an insight leading to intense individual transformation from bondage to freedom. There is no sacrifice to reason and experience, but characteristically, Indian philosophy (or Darshanas) does not have an extreme reverence for science. Indian Darshanas, unfortunately, disappeared from popular discourses because its paradigms seemed absurd to the dominant Western discourses. Additionally, western universities (especially German) aggressively pushed Indian philosophical systems as ‘religions’ and hence lacking any validity in a ‘secular’ world.

INDIC PHILOSOPHICAL SYSTEMS: BASIC FRAMEWORK AND THE ROLE OF PRAMANAS

Each of the four Vedas (Rig, Sama, Yajur, and Atharva), the earliest source of Indian thought, consist of four parts – Samhitas, Brahmanas, Aranyakas, Upanishads; the first three related to rituals and the last to philosophical speculations. They are either successive stages of Vedic literature or suggest parallel ideas. In the Brahmanas portion, ideas of monism start coming when a single supreme principle of both an immanent and transcendent power through all gods, individual souls, and nature takes hold. The Upanishidic teaching (the Vedanta portion or the ‘end of Vedas’) crystallises the notion of absolute monism which calls the Brahman as the all comprehensive only reality, the ultimate cosmic principle, the source and destination of the whole universe, and accounting for individual selves too as Atman.

The core classification of Indian systems as orthodox and non-orthodox is on the acceptance or rejection respectively of the Vedas as a reliable authority. The non-orthodox systems are Charvaka (materialism), Buddhism, and Jainism. The orthodox systems include the six systems called Samkhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisesika, Mimansa, and Vedanta. The orthodox schools come in pairs; broadly, the first pertains to practice, the second element to theory: Yoga-Samkhya; Nyaya-Vaisesika; and Mimansa-Vedanta.

Any knowledge must have certain ‘means’ of acquiring it. Pramana (proof or a valid ‘means of true knowledge’) plays an important role in Indian philosophical traditions. Ancient texts identify six pramanas whose variable acceptance and rejection form a basis for classifying the thought systems. These are:

- Perception or direct sensory experience (pratyaksha)

- Inference (anumana)

- Testimony of reliable authorities (sabda)

- Comparison and analogy (upamana)

- Postulation and derivation from circumstances (arthapatti)

- Non-perceptive negative proof (anupalabdhi).

Materialism (Lokayata or Charvaka) holds only perception as a valid pramana; Buddhism: perception and inference; and Jainism: perception, inference, and testimony. Mimamsa and Advaita Vedanta hold all six as useful means to knowledge.

Apart from materialism, both non-orthodox and orthodox schools have certain core ideas of commonality. Most important is that explanation of reality should not sacrifice reasoning and experience. Philosophy, never a dry intellectual exercise, carries a soteriological power – the power of intense individual transformation from ignorance and bondage to freedom and wisdom. There is no original sin but original ignorance. In all systems (except Charvakism), Karma is a central doctrine of cause and effect at the levels of body, mind, and intellect. Whatever one does, it has consequences, if not in this birth, then in a future birth. Karma thus intricately links to the idea of reincarnation in all systems. Moksha, a common theme for all, is the final state of enlightenment with no further births, in stark contrast to western focus for an eternal life. Almost all Indian philosophies accept perfect happiness as a state of no further births.

The practical aspects of Yoga and meditation are acceptable routes in all systems to reach the state of liberation. All stress the inability of senses or intellect to understand reality. Reality is an intuitive, non-perceptual, and non-conceptual experience. All are initially pessimistic in that they speak of ignorance and misery, but ultimately become optimistic as they give immense hope in gaining the state of eternal happiness. All focus on individual effort, if necessary, across many births to liberate from ignorance. The role of a teacher or books is only as a guide on the path, but finally, the individual’s effort is responsible for one’s own moksha, achievable in the present life.

The goal of human life in Indic philosophies firmly remains moksha or enlightenment. The journey starts from an intellectual apprehension of this goal to finally attain moksha through various routes. This is the basic framework of Indian Darshanas. The differences mainly are in the nature of the routes taken to reach there. The multiple routes are all valid like ‘various rivers merging into one ocean.’ The distinguishing feature of the varied paths is ‘an indifference to differences’ with each taking its view as the valid one (‘I am true, but you are not false’). The concept of truth stays robust in Indian traditions. There have been debates, interactions, and assimilation of ideas from across philosophies giving a richness and diversity of thought without fear of persecution. Religious clashes of the European world based on ‘truth values’ (I am true and you are false) are almost unknown in India. ‘Philosophy is dead,’ declared scientist Stephen Hawking. In the Indic context, it is relevant perennially ending only with total human freedom.

TRADITIONAL INDIAN PHILOSOPHIES ARE DARSHANAS, NOT SPECULATIVE PHILOSOPHIES

Indian Philosophy often gets the label of ‘speculative philosophy.’ Unlike in science, wherein the scientific proposition has a criterion of physical verifiability, philosophy in the West had a different criterion. It is for this reason that philosophy earned a notoriously bad name in the early years of the twentieth century when the entire field of metaphysics became ‘nonsense.’ The attack against philosophy came from the ‘Analytical Philosophers.’ Hence, in the absence of either empirically verifiable propositions or derivation out of already defined terms, metaphysical statements became meaningless.

Since metaphysics, philosophy, ethics, religion, and aesthetics are all of this nature, the only task that remained for philosophy was that of clarification and analysis. They concluded that the propositions of philosophy are linguistic, not factual, and philosophy was a department of logic. Based on such assertions, Analytical Philosophy swept aside two millennia of lofty human thought into the dustbin of ‘emotive’ thinking. Western philosophy had failed to provide a sound basis for epistemology (theory of knowledge) and it became a complex maze of verbiage that ultimately led to the discrediting of everything metaphysical and of philosophy herself, says Chittaranjan Naik (Apaurusheyatva of the Vedas).

In traditional Indian Philosophy, assertions about the objects of the world ground either in perception or in inference. Hence, there is no scope for these assertions to stray into speculative thought. If they do stray, it is only due to the incorrect application of the pramanas and not due to the nature of the philosophy itself. And when it comes to assertions about things that lie beyond the range of the senses, the assertions ground in Scriptural sentences (Shabda) and in inferences that depend entirely on these scriptural sentences. If they do stray here too, it is again due to an incorrect understanding of the scriptural sentences or the inferences drawn from them. There is a lot of misconception about Indian Philosophy that comes from modern authors, both Indian as well as Western.

Traditional Indian Darshanas are not something derived from basic principles to finally arrive at a conclusion. As Naik says: A Darshana is a Single Vision in which all its elements including epistemology, ontology, metaphysics, the practice, and the fruits of sadhana are like various organs that form a single integral whole. Each of the traditional philosophies or Darshanas is eternal and is part of the Vedic structure. That is why they constitute one of the fourteen branches of learning (vidhyasthanas) known as Chaturdasa Vidyas. ‘Darshana’ strictly is not synonymous with ‘philosophy.’ However, to avoid confusion and when seen as intellectual activity contemplating the world around us, one can broadly consider them as equivalent terms.

NON-VEDIC SCHOOLS

Charvakism or Lokayata: Materialism

Sage Charvak’s ancient Indian tradition, pre-Buddhist and post-Upanishadic, are known mainly from its criticism in later works. For a materialist, only pratyaksha (perception) is the single valid criteria for knowledge. The major criticism against materialism is that despite rejecting inference, implying rejecting generalizations, their own practice in dealing with the world (a generalization that ‘perception and only perception’ is reliable) contradicts that stand. For them, God, souls, heaven, hell, and immortality are non-existent. Matter is the only reality and the world forms by a combination of primordial elements- earth, air, fire, and water; it rejects akasa (ether) as an element. Consciousness is secondary to matter. Nature is enough to explain creation, sustenance, and destruction. Death is the final annihilation with no further births. Of the four Purusharthas, the ends of human life – dharma (right conduct in the broadest sense), artha (wealth), kama (desire), and moksha (liberation), only the pursuit of pleasure and enjoyment of possessions remain sensible ends to life.

Importantly, Charvakism or Lokayata is not the crude hedonism we tend to associate with the materialists. There were certain ethics in that pleasure should not be at the cost of pain and misery. It was also altruistic. They recognized the need for society, law, and order and certainly did not advocate an anarchic society based on an unbridled catering to the senses. The philosophy tempered with self-discipline, intelligence, refined taste, and a genuine capacity for friendship, says Ramakrishna Puligundla (Fundamentals of Indian Philosophy). Amazingly, in Indian society, Charvaks since antiquity had no issues of persecution by the non-Charvaks of any kind.

Jainism

Prince Vardhaman (540 BCE- 468 BCE), twenty-fourth in the line of perfect souls (Tirthamkaras), popularised Jainism and was not its founder. Unlike Buddhism, Jainism stayed in India where it is still a thriving tradition. There are minor doctrinal differences between the two main sects of Jains – the Svetambaras and the Digambaras. The seven principles of Jainism are: Jiva (soul), Ajiva (matter), Asrava (movement of Karma), Bandha (bondage), Samvara (karma-check), Nirjara (falling off Karma), and Moksa (liberation). Jainism is dualistic-pluralism. The two distinct categories of substances- animate (jivas or souls) and inanimate (ajivas or non-souls), make up for its dualism. Pluralism is the infinite number of substances.

The substance (dravya) has either ‘essential’ gunas (eternal and unchanging) or ‘accidental’ paryayas (allowing for impermanence). Hence, both change and permanence are real features of all existence. For example, the ‘soul’ in Jain conception has the essential feature of consciousness and the accidental feature of pain and pleasure. All substances (souls, matter, space, dharma, adharma, and so on) except Time (kala) extend into space. Time is the only ajiva which is infinite and all-pervasive where all things and changes take place. The universe has no beginning or end; it is an endless cycle of creation and destruction.

Souls grade on the sense organs they possess. Plants have only touch and are the lowest; the soul of man has six, including the mind, and is most evolved. The whole universe is thus throbbing with souls. Jiva, the eternal substance with the essential properties of consciousness and knowledge, is atomic and capable of change in magnitude. The sense organs and material body, attaching as karmic particles, are obstacles for the soul (Jiva) to gain primordial omniscience. The goal of life is to remove the limitations of matter and reach the state of pure, perfect, and all-encompassing knowledge. Jainism upholds karma, rebirth, and transmigration of souls. Any soul can achieve liberation by self-effort, discipline, prayer, worship, austerity, simple life, extreme non-violence, compassion, and truthfulness. Jainism rejects God as a creator believing nature is enough to account for the universe. Jainism rejects both the unchanging Brahman of Upanishads or the ‘absolute change’ devoid of anything permanent (Buddhism).

Buddhism

Prince Gautama (563 BCE-486 BCE) following his enlightenment became the Buddha. His teachings form the basis of Buddhist tradition. The rich and vast Buddhist literature divides into many traditions but two are important: the Hinayana in Pali language and the Mahayana in Sanskrit. The core of the former is the Pali Canon, the original teachings of Buddha after his enlightenment. The Four Noble Truths formed the subject of the first sermon Buddha delivered at Benares:

- Life is evil and full of pain and suffering

- The origin of all evil is ignorance (avidya) – not knowing the true nature of the self. The feeling of self as apart from the body-mind complex is false and it is undergoing constant change. Nirvana is cessation of this change. The clinging to the false self is the reason for all misery in life.

- There are twelve links in the ‘chain of causation’ of evil. This chain starts with ignorance leading to a craving. The unfulfilled cravings lead to repeated cycles of rebirth and deaths. Breaking from this karmic chain of repeated lives, one attains a state of serene composure – Nirvana.

- Right knowledge (prajna) is the means of removing evil. Right conduct was a means to right knowledge in the original teaching.

The recommended middle path of Buddha for everyone was devoid of severe austerities. Right conduct (sila), right knowledge (prajna), and right concentration (samadhi) are the most important. The rest five of the ‘Eight-Fold Path’ is for those entering the order of ascetics. Buddhism, spreading to other countries broke up into many schools of thought. Common to the main two creeds is the most important doctrine of momentariness. Everything continues as a series for any length of time giving the illusion of continuity. Regarding differences, Hinayana school was atheistic looking at the Buddha as a human being but divinely gifted; the Mahayana deified Buddha with elaborate worship rituals.

The Mahayana school in turn has two doctrines: the Yogachara and the Madhyamika. The former, akin to the modern subjective idealism, reduces all reality to only thought with no external objective counterpart. Madhyamika is nihilism which denies reality of both the external world and the self too. The Madhyamika school hence maintains the important doctrine of sunya-vada -the ultimate reality is the void or vacuity-in-itself. Hinayana Buddhism and the Yogachara doctrine of Mahayana Buddhism admit to an Absolute Consciousness, a positive ground for all experience. The goal of life would be to merge in this Absolute. The Madhyamika doctrine rejects any positive ground and the goal is annihilation of all illusion into a void. However, the enlightened person (Bodhisattva) still works for the good of society.

VEDIC OR ORTHODOX SCHOOLS

Nyaya-Vaisesika

Nyaya system is the most systematic application of logic in the acquisition of knowledge (epistemology). Vaisesika is an explanation of the reality around us (ontology), beginning with the description of the indestructible atoms as the basis of all reality. Though arising independently, gradually they merged for common study. In its classical form, Nyaya accepted four sources of valid knowledge (perception, inference, comparison, and testimony); the Vaisesika, only two (perception and inference). Gautama (not to be confused with Buddha) founded the Nyaya school in 3rd century BCE; later modifications resulted in the modern school – Navya Nyaya, by Gangesa in 1200 CE.

As the shortest description, Nyaya is logical realism and atomic pluralism. Logic and critical thinking can defend that the physical reality is independent of our awareness not requiring belief, faith, or intuition. Atoms constitute matter and the pluralism stems from the idea there is not one but many entities (material and spiritual) as ultimate constituents of the universe. Nyaya studies philosophy under sixteen categories (padarthas), which includes objects for knowledge (prameyas), the means for knowledge (pramanas), and the purpose of such knowledge.

Thus, the Nyaya system studies the Self; the body; the senses; the objects of the senses; the mind, knowledge, and activity; mental imperfections; rebirth; pleasure and suffering; freedom from suffering; substance; quality; motions; universals (samanya); particulars (visesa); inherence (samavaya); and non-existence (abhava).

Nyaya develops the most elaborate rules of logic for acquisition of knowledge. Indian logic is an instrument for the understanding and discovery of reality quite unlike Western logic- a formal structural inquiry unrelated to the world. The Self is an individual substance- eternal, all pervading, and non-physical; pure consciousness is only an accidental attribute of the Self (unlike Advaita). The aim of Nyaya is liberation of the Self from the bondage and suffering due to its association with the body. Knowledge arising from listening (sravana), intellectual comprehension (manana), and Yogic meditation (nidhidhyasana) leads to cessation of all activity related to the body and thus to liberation. Though there was no focus on God initially, later Nyaya works, especially Udayana’s Nyayakusumanjali, offers proofs for the existence of God from different perspectives including atomism.

Kanada was the founder of Vaisesika system and later authors like Prasastapada and Sridhara wrote commentaries. As old as Jainism and Buddhism, it is also known as the ‘atomistic school’ because of its elaborate atomic theory to explain the universe. However, Vaisesika has a central tenet of particulars (vaisesas) constituting all of existence, out of which some are atomic and some are non-atomic.

Vaisesika, as a philosophy for ontology (explanation of universe), is pluralistic realism. Pluralism, because it holds the universe consisting of a combination of a variety and diversity of irreducible elements. Realism, because it holds reality as independent of our perceptions. Vaisesika recognizes seven padarthas or categories (included in the sixteen of Nyaya) to comprehend the objects making up the world.

Substance (dravya) is the substratum in which qualities and action exist. There are nine ultimate substances in total: five material (earth, water, fire, air, and akasa) and four non-material (space, time, soul, and mind). Material substances except akasa exist as indivisibles called paramanus (atoms), known only through inference. Two atoms combine to form a dyad; three dyads combine to form a triad, the smallest perceptible object. Everything material in the universe is a combination of these triads. Akasa (ether) is non-atomic, all-pervading, and infinite. Only composites made of different combinations of earth, air, fire, and water atoms are perceivable; and being a composite, are transient and impermanent.

The non-material substances – time, space, mind, and soul are indivisible, all-pervading, and eternal. All the non-material substances are known by inference only except the soul known only by direct perception. The most important idea of Vaisesika is the property of ‘particularity’ (or vaisesas) of the indivisible and eternal substances- atoms, akasa, space, time, souls, and minds. This particularity does not extend to composite objects like tables and chairs. Vaisesika also focusses on samayoga and samvaya between two conjoint objects. Samayoga (a book on a table) is temporary, mechanical, external relation between objects coming together when there is no destruction of the components on separation. Samavaya is a conjoint existence of objects, where separation implies destruction of the component objects. Thus, samavaya is necessary, eternal, and internal relation.

Vaisesika maintains the asatkaryavada view of causation- the effect does not pre-exist in the cause. God is co-existent with the eternal atoms and becomes only a designer of the universe by giving a push to these atoms. Hence, atoms and other substances are the material cause of the universe; and God is its efficient cause. Existence is bondage and ignorance where the soul falls prey to desire and passion to identify itself with the non-soul. Like in all other schools, knowledge is the means to freedom and liberation; and the way to break the karmic chain is cessation of action. In contrast to Advaita, the Vaisesika conception of liberation is a state beyond both pleasure and happiness, a substance devoid of any attributes including consciousness. The points of criticism in Vaisesika are its conception of God and the state of the liberated soul.

Samkhya-Yoga

Samkhya, one of the oldest schools pre-dating Buddha, founded by Sage Kapila, influenced all other orthodox and non-orthodox Indian schools significantly. The earliest of the many commentaries is Samkhya-Karika of the 5th century CE. Samkhya philosophy, summarized as dualistic realism, has two equal and ultimate realities: Purusa (Self or spirit), the eternal experiencing subject and Prakriti (matter), the eternal experienced object. Both Samkhya and Yoga recognise three sources of knowledge: perception, inference, and testimony.

Prakriti is the first cause of all objects of the universe including the body, senses, mind, and the intellect. It is uncaused, eternal, all-pervading, and being subtlest – unperceivable; inferred only by its effects. Prakriti, a dynamic mix of three component essences called sattva (purity), rajas (action), and tamas (ignorance and heaviness), manifests as objects of experience (gross or material) for Purusa. Change and activity are the essence of prakriti.

Samkhya holds the satkaryavada theory of causation where the effect is identical with the cause. The three components sattva, rajas, and tamas are present in each object producing pleasure, pain, or indifference in us depending on the relative amount of each component. Dissolution into the primordial cause following evolution of matter leads to cosmic cycles of creation and destruction. The intellect (mahat), ego (ahamkara), and mind (manas) arise in succession from sattva first. This complex is the internal organ or antah-karana, the basis of our mental life.

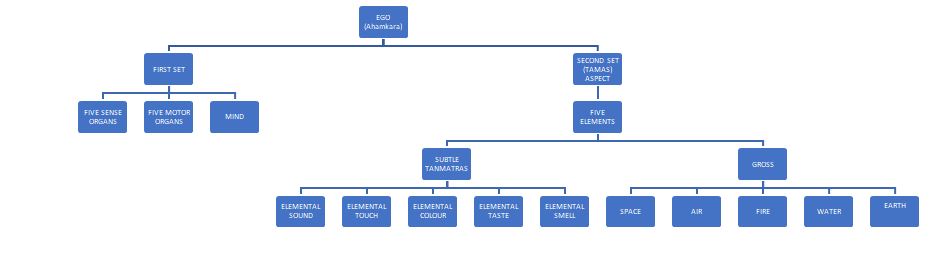

Ahamkara or ego, from which two sets of objects emanate, is the central reason for the entire world. The first set consists of the five sense organs, the five motor organs, and the mind. The second set, emanating from the tamas aspect, comprises five elements that again exist in two forms – subtle and gross. The five subtle elements (tanmatras) give rise to the five gross elements by combinations. The five tanmatras are elemental sound, elemental touch, elemental colour, elemental taste, and elemental smell. Elemental sound gives rise to space; sound and touch combine to form air; sound, touch, and colour combine to form fire; sound, touch, colour, and taste give rise to water; and all five combine to form earth. Depending on the constituent tanmatras, the gross acquires its properties. Evolution and dissolution go on constantly.

Purusa (the Self within), the second ultimate reality, is pure consciousness or sentience separate from the insentient prakriti. Purusa is a pure subject, never an object of our intellect or mind, and whose existence is only by inference. The important argument for the existence of the Self is the most indubitable and incontrovertible experience of one’s own existence. Samkhya believes in the plurality of purusas- a spiritual pluralism. No two humans are mentally and morally identical. Regarding purposes, Samkhya explains by saying that it is ignorance on part of the purusa to get attachment to prakriti; and liberation consists in the knowledge of its absolute and eternal independence from the latter. The liberating knowledge is total independence of the self from the non-self, a state beyond joy and sorrow. Moral perfection is a necessity to achieve this salvation or a state of absolute freedom (kaivalya) from further births. The means of achieving this is through Yoga.

Yoga, as a system of philosophy, closely attaches to Samkhya. Amazingly, despite theoretical differences, all Indian schools, except Charvaka, recommend and recognize Yoga as important means to attain liberation. Yoga differs from Samkhya importantly in the consideration of a Supreme Purusa (or Ishwara, God or the Self) above all the individual selves of Samkhya. The Supreme Purusa guides contact of individual purusa and prakriti to help in the evolution of varying degrees of perfection of purusa. The upper limit of perfection is the Supreme Purusa. Patanjali, not particularly recognizing God in his scheme, however, taught devotion to God for surrendering egoism, the biggest obstacle in the realization of Truth.

Yoga aims for knowledge to free an individual from the shackles of prakriti, most importantly the intellect, mind, and senses. The Yoga-sutras of Patanjali, the first authoritative exposition laying the theoretical and practical foundations, has had many important commentaries later. Yoga has an eight-fold (Astanga-Yoga) path on the route to perfection of an individual. The first five limbs are yama, niyama (control of desires and emotions), asana, pranayama (physical and breath exercises to have a healthy body), and pratyahara (detaching sense organs from the mind). These five are pre-requisites for the further stages of dharana (concentrated focus on limited objects), dhyana (total focus of the mind on a single object). The final stage is Samadhi- the state of pure consciousness where the mind completely dissolves with disappearance of brain-bound intellect.

Can the intuitive knowledge so obtained be a basis for intellectual knowledge, such as that of science? There are two stages again of Samadhi- the savitarka (with its three knowledge components of sabda, artha, and jnana) and the nirvitarka. In the jnana state of the former, knowledge based on perception and reasoning can build conceptual knowledge. In the nirvitarka, the complete Yogi has an instantaneous cognition and complete knowledge of the manifested universe. The state of pure subjectivity is kaivalya or liberation. Yoga is thus a wonderful whole much more than the physical exercises.

There is a needless discussion on whether Yoga is Indian or is it universal like the law of gravity by prominent personalities on both sides of the fence. The confusion mainly arises from the universal application of the asanas and pranayama in achieving the physical health of the human body. In that respect of a narrow domain understanding of a purely physical aspect Yoga definitely is universal and applicable to any human being. But Yoga as a comprehensive philosophy is definitely Indian where its application leads to moksha or liberation. As regards the origin, Yoga is Indian without any compromise and to give examples like gravity is misleading. There is no confusion, the circles of modern western science, about Newton being the one who discovered gravity.

In the next part, we shall review the most important Darshanas- Mimansa and Vedanta, which dominates Indian traditional thinking. We shall also see some important ideas in Indian philosophy and how the so-called antagonism between the orthodox and non-orthodox schools is a figment of overworked imagination arising especially in the western academia.

Continued in Part 2

Leave a Reply