Views expressed in a time gone by about the state of India's education system still resonate loudly and perhaps are even more true now, than they were then.

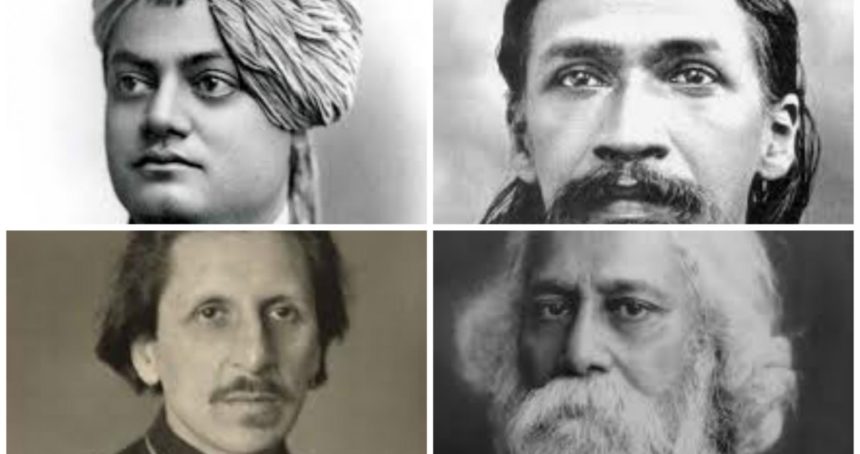

Great Minds on Indian Education System

Swami Vivekananda

The child is taken to school, and the first thing he learns is that his father is a fool, the second thing that his grandfather is a lunatic, the third thing that all his teachers are hypocrites, the fourth, that all the sacred books are lies! By the time he is sixteen he is a mass of negation, lifeless and boneless. And the result is that fifty years of such education has not produced one original man in the three presidencies…. We have learnt only weakness.[1]

Out of the past is built the future. Look back, therefore as far as you can drink deep of the eternal fountains that are behind and after that look forward, march forward and make India brighter, greater, much higher than she ever was. Our ancestors were great. We must first recall that. We must learn the elements of our being, the blood, that courses in our veins; we must build an India yet greater than what she has been.[2]

Nowadays everybody blames those who constantly look back to their past. It is said that so much looking back to the past is the cause of all India’s woes. To me, on the contrary, it seems that the opposite is true. So long as they forgot the past, the Hindu nation remained in a state of stupor and as soon as they have begun to look into their past, there is on every side a fresh manifestation of life. It is out of this past that the future has to be moulded, this past will become the future.

The more, therefore, the Hindus study the past, the more glorious will be their future and whoever tries to bring the past to the door of everyone, is a great benefactor to his nation. The degeneration of India came not because of the laws and customs of the ancients were bad but because they were not allowed to be carried to their legitimate conclusions.[3]

Study Sanskrit, but along with it study Western sciences as well. Learn accuracy, my boys, study and labour so that the time will come when you can put our history on a scientific basis… The histories of our country written by English writers cannot but be weakening to our minds, for they talk only of our downfall. How can foreigners, who understand very little of our manners and customs, or our religion and philosophy, write faithful and unbiased histories of India? Naturally many false notions and wrong inferences have found their way into them. Nevertheless they have shown us how to proceed making researches into our ancient history. Now it is for us to strike out an independent path of historical research for ourselves, to study the Vedas and Puranas and the ancient annals (Itihasas) of India, and from them make it your sadhana to write accurate, sympathetic and soul-inspiring history of India. It is for Indians to write Indian history.[4]

We must compile some books in Bengali as well as in English with short stories from the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, and the Upanishads etc., in very easy and simple language, and these are to be given to our little boys to read.[5]

… You never cease to labour until you have revived the glorious past of India in the consciousness of the people. That will be the true national education, and with its advancement, a true national spirit will be awakened.[6]

Education must take a form which is compatible with the national character.[7}

Sri Aurobindo

We in India have become so barbarous that we send our children to school with the grossest utilitarian motive unmixed with any disinterested desire for knowledge; but the education we receive is itself responsible for this…. The easy assumption of our educationists that we have only to supply the mind with a smattering of facts in each department of knowledge and the mind can be trusted to develop itself and take its own suitable road is contrary to science, contrary to human experience…. Much as we have lost as a nation, we have always preserved our intellectual alertness, quickness and originality; but even this last gift is threatened by our University system, and if it goes, it will be the beginning of irretrievable degradation and final extinction. The very first step in reform must therefore be to revolutionise the whole aim and method of our education.[8]

When confronted with the truths of Hinduism, the experience of deep thinkers and the choice spirits of the race through thousands of years, [the rationalist] shouts “Mysticism, mysticism!” and thinks he has conquered. To him there is order, development, progress, evolution, enlightenment in the history of Europe, but the past of India is an unsightly mass of superstition and ignorance best torn out of the book of human life. These thousands of years of our thought and aspiration are a period of the least importance to us and the true history of our progress only begins with the advent of European education![9]

In India … we have been cut off by a mercenary and soulless education from all our ancient roots of culture and tradition…. The value attached by ancients to music, art and poetry has become almost unintelligible to an age bent on depriving life of its meaning by turning earth into a sort of glorified ant-heap or beehive.[10]

National education cannot be defined briefly in one or two sentences, but we may describe it tentatively as the education which starting with the past and making full use of the present builds up a great nation. Whoever wishes to cut off the nation from its past is no friend of our national growth. Whoever fails to take advantage of the present is losing us the battle of life. We must therefore save for India all that she has stored up of knowledge, character and noble thought in her immemorial past. We must acquire for her the best knowledge that Europe can give her and assimilate it to her own peculiar type of national temperament. We must introduce the best methods of teaching humanity has developed, whether modern or ancient. And all these we must harmonise into a system which will be impregnated with the spirit of self-reliance so as to build up men and not machines.[11]

The greatest knowledge and the greatest riches man can possess are [India’s] by inheritance; she has that for which all mankind is waiting…. But the full soul rich with the inheritance of the past, the widening gains of the present, and the large potentiality of the future, can come only by a system of National Education. It cannot come by any extension or imitation of the system of the existing universities with its radically false principles, its vicious and mechanical methods, its dead-alive routine tradition and its narrow and sightless spirit. Only a new spirit and a new body born from the heart of the Nation and full of the light and hope of its resurgence can create it…. The new education will open careers which will be at once ways of honourable sufficiency, dignity and affluence to the individual, and paths of service to the country. For the men who come out equipped in every way from its institutions will be those who will give that impetus to the economic life and effort of the country without which it cannot survive in the press of the world, much less attain its high legitimate position. Individual interest and National interest are the same and call in the same direction.[12]

A language, Sanskrit or another, should be acquired by whatever method is most natural, efficient and stimulating to the mind and we need not cling there to any past or present manner of teaching: but the vital question is how we are to learn and make use of Sanskrit and the indigenous languages so as to get to the heart and intimate sense of our own culture and establish a vivid continuity between the still living power of our past and the yet uncreated power of our future, and how we are to learn and use English or any other foreign tongue so as to know helpfully the life, ideas and culture of other countries and establish our right relations with the world around us. This is the aim and principle of a true national education, not, certainly, to ignore modern truth and knowledge, but to take our foundation on our own being, our own mind, our own spirit.[13]

The living spirit of the demand for national education no more requires a return to the astronomy and mathematics of Bhaskara or the forms of the system of Nalanda than the living spirit of Swadeshi a return from railway and motor traction to the ancient chariot and the bullock-cart…. It is the spirit, the living and vital issue that we have to do with, and there the question is not between modernism and antiquity, but between an imported civilisation and the greater possibilities of the Indian mind and nature, not between the present and the past, but between the present and the future. It is not a return to the fifth century but an initiation of the centuries to come, not a reversion but a break forward away from a present artificial falsity to her own greater innate potentialities that is demanded by the soul, by the Shakti of India.[14]

Ananda Coomaraswamy

One of the most remarkable features of British rule in India has been the fact that the greatest injuries done to the people of India have taken the form of blessings. Of this, Education is a striking example; for no more crushing blows have ever been struck at the roots of Indian National evolution than those which have been struck, often with other, and the best intentions, in the name of Education…. The most crushing indictment of this Education is the fact that it destroys, in the great majority of those upon whom it is inflicted, all capacity for the appreciation of Indian culture. Speak to the ordinary graduate of an Indian University, or a student from Ceylon, of the ideals of the Mahabharata:he will hasten to display his knowledge of Shakespeare; talk to him of religious philosophy; you find that he is an atheist of the crude type common in Europe a generation ago, and that not only has he no religion, but he is as lacking in philosophy as the average Englishman; talk to him of Indian music; he will produce a gramophone or a harmonium, and inflict upon you one or both; talk to him of Indian dress and jewellery; he will tell you that they are uncivilized and barbaric; talk to him of Indian art; it is news to him that such a thing exists; ask him to translate for you a letter written in his own mother-tongue; he does not know it. He is indeed a stranger on his own land.[15]

It is hard to realize how completely the continuity of Indian life has been severed. A single generation of English education suffices to break the threads of tradition and to create a nondescript and superficial being deprived of all roots — a sort of intellectual pariah who does not belong to the East or the West, the past or the future. The greatest danger for India is the loss of her spiritual integrity. Of all Indian problems the educational is the most difficult and most tragic.[16]

The two great Indian epics have been the great medium of Indian education, the most evident vehicle of the transmission of the national culture from each generation to the next. The national heroic literature is always and everywhere the true basis of a real education in the formation of character.[17]

A great and real responsibility rests upon those who control education in the East, to preserve in their systems the fundamental principles of memory-training and mental concentration which are the great excellence of the old culture.[18]

Rabindranath Tagore

All over India, there is a vague feeling of discontent in the air about our prevalent system of education.

The mind of our educated community has been brought up within the enclosure of the modern Indian educational system. It has grown as familiar to us as our own physical body, unconsciously giving rise in our mind to the belief that it can never be changed. Our imagination dare not soar beyond its limits; we are unable to see it and judge it from outside. We neither have the courage nor the heart to say that it has to be replaced by something else….

They [Indian students] never have intellectual courage, because they never see the process and the environment of those thoughts which they are compelled to learn and thus they lose the historical sense of all ideas, never knowing the perspective of their growth…. They not only borrow a foreign culture, but also a foreign standard of judgement; and thus, not only is the money not theirs, but not even the pocket. Their education is a chariot that does not carry them in it, but drags them behind it. The sight is pitiful and very often comic.

The education which we receive from our universities takes it for granted that it is for cultivating a hopeless desert, and that not only the mental outlook and the knowledge, but also the whole language must bodily be imported from across the sea. And this makes our education so nebulously distant and unreal, so detached from all our associations of life, so terribly costly to us in time, health and means, and yet so meagre of results.

We must know that this concentration of intellectual forces of the country is the most important mission of a University, for it is like the nucleus of a living cell, the centre of creative life of the national mind.

The same thing happens in the case of our Indian culture. Because of the want of opportunity in our course of study, we take it for granted that India had no culture, or next to none. Then, when we hear from foreign pundits some echo of the praises of India’s culture, we can contain ourselves no longer and rend the sky with the shout that all other cultures are merely human, but ours is divine a special creation of Brahma! And this leads us to that moral dipsomania, which is the hankering after the continual stimulation of self-flattery.

… The inner spirit of India is calling to us to establish in this land great centres, where all her intellectual forces will gather for the purpose of creation, and all her resources of knowledge and thought, Eastern and Western, will unite in perfect harmony. She is seeking for herself her modern Brahmavarta, her Mithila, of Janaka’s time, her Ujjaini, of the time of Vikramaditya. She is seeking for the glorious opportunity when she will know her mind, and give her mind to the world, to help it in its progress; when she will be released from the chaos of scattered powers and the inertness of borrowed acquisition. [19]

What I object to is the artificial arrangement by which this foreign education tends to occupy all the space of our national mind and thus kills, or hampers, the great opportunity for the creation of a new thought power by a new combination of truths. It is this which makes me urge that all the elements in our own culture have to be strengthened, not to resist the Western culture, but truly to accept and assimilate it, and use it for our food and not as our burden; to get mastery over this culture, and not to live at its outskirts as the hewers of texts and drawers of book-learning.

My suggestion is that we should generate somewhere a centripetal force, which will attract and group together from different parts of our land and different ages all our own materials of learning and thus create a complete and moving orb of Indian culture.

The main river of Indian culture has flowed in four streams: the Vedic, the Puranic, the Buddhist, and the Jain. It had its source in the heights of the Indian consciousness.

… Our mind is not in our studies. In fact, it has been wholly ignored that we have a mind of our own.

India has proved that it has its own mind, which has deeply thought and felt and tried to solve according to its light the problems of existence. The education of India is to enable this mind of India to find out truth, to make this truth its own wherever found and to give expression to it in such a manner as only it can do.

References / Footnotes

1 Swami Vivekananda’s Complete Works, Vol. III, p. 301-02.

2 CW, Vol. III, p. 285-86.

3 CW, Vol. IV, p. 324.

4 CW, Vol. III, p. 302.

5 CW, Vol. V, p. 301.

6 CW, Vol. III, p. 302.

7 CW, Vol. III, p. 302.

8 Sri Aurobindo Birth Centenary Library (Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry, 1972), 3.125-127.

9 India’s Rebirth (Mira Aditi, Mysore, 2000, 3rd edition), p. 55.

10 India’s Rebirth, p. 65

11 India’s Rebirth, p. 38

12 Extracts from a “Message on National Education” published in New India of April 8, 1918, a journal edited by Annie Besant.

13 Sri Aurobindo Birth Centenary Library (Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry, 1972), 17.194-196.

14 From an article entitled “A Preface on National Education,” India’s Rebirth, (Mira Aditi, 3rd ed. 2000), p. 156.

15 National Idealism, p. 96-97.

16 The Dance of Shiva (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1997, p. 170).

17 National Idealism, p. 119.

18 National Idealism, p. 124.

19 From The Centre of Indian Culture (Visva Bharati, 1988 reprint).

Leave a Reply